From Idea to Manufacturing: The Journey to COR ZERO's Launch in the 3D Printing Space

How The COR ZERO Kickstarter campaign aims to revolutionize the 3D printing space by transforming makers into manufacturers.

COR Zero: 4000 Days to Launch

For many innovators, launching a Kickstarter campaign is pretty much "Day 1" of their entrepreneurial journey.

For me, today's launch is closer to Day 4000.

About ten years ago, a mentor told me that it takes at least ten years to bring a new material to market. I was still in graduate school at Caltech and feeling pretty good about my latest invention. I thought to myself "yeah yeah, I bet I can do it in five".

This is the story of why it took 4000 days to launch COR Zero, our latest rugged resin that enables you to 3D print truly manufacturing-grade parts in your home workshop.

Caltech

Almost exactly 4000 days ago, the Journal of the American Chemical Society published my paper "Photolithographic Olefin Metathesis Polymerization", which described a fundamentally new type of photopolymer resin, based on a mechanism called "olefin metathesis".

I won't explain why I really wanted my mechanism to be called "PLOMP", but I will share that new chemical mechanisms typically fit squarely into what one might call a "platform technology".

Bob Grubbs used to say that they need a different business school for platform technologies, and around this same time, I was also taking my first "business school" courses. Caltech doesn't have a business school, so they flew in instructors to teach high tech entrepreneurship, including the legendary Ed Zschau. (In case you are curious, here is an amazing interview with Ed on the Tim Ferriss Show)

To put it bluntly: I had a solution, in search of a problem.

Cyclotron Road

In the summer of 2014, I was trying to figure out what I was going to do when I graduated. I had been thinking that I would be a professor, when an application for a brand-new fellowship program called "M37" came out. I had three or four different people send this application link to me, saying I would be a perfect fit. The application was due in a month, and I spent three out of those four weeks thinking this was weird, but I finally decided to apply.

Crazy things happened in Berkeley. "M37" became "Cyclotron Road" became "Activate". I got to challenge Rick Perry to a 3D-printed wishbone competition and meet Bill Gates. I could write a book about those two years and maybe I will after this Kickstarter is over, but the key skill I started to learn during the fellowship (that they don't teach you in graduate school) is risk management.

We had a solution in search of a problem, a platform technology, and there was a lot of risk involved in bringing it to market.

But which market? We decided to go all-in on 3D printing.

When we started at Cyclotron Road (now the Activate Fellowship), we really had no idea if PLOMP would work on a 3D printer.

There were three reasons that we chose 3D printing. The first was rational: it was a fast-growing market that was mature enough for a startup to find a foothold, but not so mature that the industry had already consolidated. The second reason we chose 3D printing was irrational: we were chasing a Holy Grail.

Chasing The Holy Grail of Polymer 3D Printing

Both the Activate Fellowship and the NSF I-CORPS program forced us to get "out of the lab" and talk to people. I didn't have a problem talking to people. What I quickly learned was that the real skill they don't teach you in graduate school is listening to people.

So we set up a lot of meetings and tried to do as much listening as possible. And in these meetings, we were told of a "Holy Grail". The Holy Grail of Polymer 3D Printing.

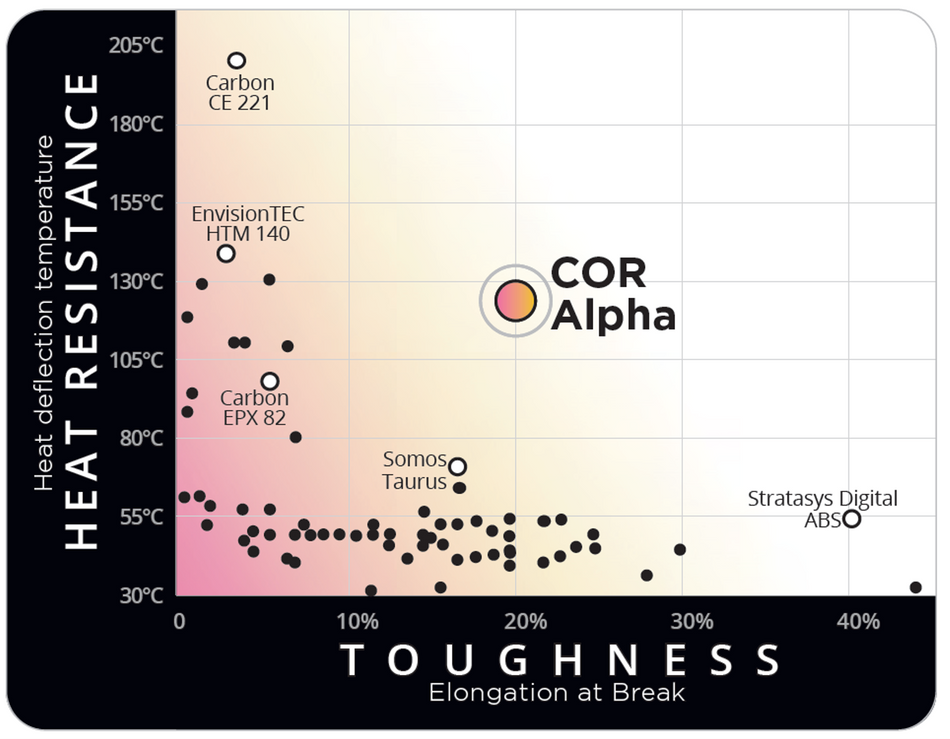

The old-school stereolithography resins were brittle and had low working temperatures. As we were starting to spin polySpectra out of Cyclotron Road, there was starting to be some progress on one or the other, but no one could do both.

The problem is that the whole reason that plastics are used ubiquitously is that they have both properties. Thermoplastic parts aren't going to melt or deform in a hot car and they aren't going to shatter if you drop them on the floor. Fused Deposition Modeling could use the same polymers as injection molding, but the process was cursed with poor resolution, a lack of sealed-surfaces, and the infamous "Z-Strength" problem of wildly anisotropic parts (not to mention path-dependent materials properties).

The bar is so low, in fact, that unfortunately this slide is still true:

So "tough and hot at the same time" was the Holy Grail. That was easy for our olefin metathesis to do, but now we had to figure out how to get our chemistry to work in a 3D printer.

This turned out to be really hard. There weren't any open printers available. The Autodesk Ember was the only open printer that we were aware of, but they were unfortunately ahead of their time and, as a software company, couldn't maintain their commitment to a hardware product. Autodesk was our first printer partner, but unfortunately they quickly shuttered the Ember.

Initially, our 3D printing resins based on PLOMP (which we named COR for Cyclic Olefin Resin) needed to be printed in a nitrogen atmosphere. We partnered with Asiga to develop a special gas edition of their Pro 4K printer that could be filled with inert gas and maintain an atmosphere with a specified range of oxygen.

Next, we figured out how to make our resins print in air, but then we needed the post-baking process (necessary to achieve our very high working temperatures) to be in a vacuum oven. Eventually, we solved the vacuum oven requirement with waveCure.

For the longest time, our resins only worked on 385 nanometer printers. The vast majority of resin printers in the world are at 405 nanometers. A few year ago, we finally figured out how to make it work at 405 nanometers.

Making It Real

In many ways, we did it. Iterating over many years, we Holy-Grailed. Woo!

But you might remember that I said there were three reasons that we chose 3D printing as our market. The first was rational - "good market dynamics". The second was irrational - a "Holy Grail" problem our platform technology could solve.

The third reason was extremely personal. Spiritual perhaps.

Along the way, I realized that this thing I had invented could actually help other people with their inventions. The floodgate keeping "3D printing" from becoming "additive manufacturing" was a materials chemistry problem, and if we could solve that problem, then we could dramatically lower the cost of innovation in durable goods.

The mission: empower engineers to make their ideas real with the world's most rugged resins.

Now perhaps you can start to see how this comes full circle to Kickstarter.

Why do innovators need Kickstarter? Because manufacturing is expensive! Because they need to pay for injection molding tooling!

In other words: the kind of engineer that is going to be the most empowered by COR Zero isn't working for GE or GM or Google.

The kind of engineer who can make their ideas real 10x- or even 100x-faster with COR than with traditional manufacturing doesn't have a network of contract manufacturers in Asia.

The kind of engineer who would be really empowered by this innovation is the kind of engineer that would start a Kickstarter.

...and unfortunately, for most of the history of polySpectra, we've needed to turn those kinds of people away. This was painful, but the resin simply wasn't safe for individuals to use at home.

(I have a much longer safety rant on other 3D printing resins that absolutely should not be allowed to be shipped to residential addresses, but I will try to keep this piece focused on the positive.)

Making COR Safe Enough for At-Home Use

The final innovation that led to COR Zero was all about reducing the safety requirements. We had figured out how to run the process on inexpensive equipment, but unfortunately only if that equipment was in an expensive building.

Some back-story: the closest well-known analogs to COR are poly(dicyclopentadiene) thermosets. These high-performance materials have been around for a long time and they played a major role in getting me excited about materials chemistry as an adolescent. (Bullet-proof panels and baseball bats were about the coolest things imaginable to me as a middle-school boy.)

While olefin metathesis is safer than photo-radical or cationic polymerizations in many ways, dicyclopentadiene (DCPD) itself has an incredibly low odor detection threshold. The final printed parts are incredibly safe, and you can safely work with DCPD with appropriate PPE and ventilation. However, DCPD is really not something that should be used at home, it demands professional infrastructure and attention to detail. Over our history as a company, we've worked to minimize the amount of DCPD in our formulations, but until recently, we thought it would be impossible to remove completely.

Thankfully, we were wrong. We managed to remove DCPD entirely, there is none in COR Zero. Funny enough, as soon as the dicyclopentadiene was gone, COR Zero became one of the safest resins out there. We're still finalizing the COR Zero SDS, but I frankly can't believe how few hazard statements there will be.

However, in order to actually sell COR Zero, we had to figure out how to make a new molecule: tricyclopentadiene (TCPD). TCPD is super safe by comparison, and is even used in fragrances. Depending on who you ask, it has a faint smell of either soap or cilantro, I personally imagine a cilantro powdered detergent.

The challenge with TCPD: no one in the world sells it. (If you find someone, let me know ;) )We figured out how to make it, and we've lined up the entire supply chain. Our Kickstarter campaign is all about crowd-sourcing the purchasing power that we need to make COR Zero inexpensive enough for individual innovators.

The founding thesis of polySpectra was that the only thing keeping "3D printing" from being true "additive manufacturing" was the materials. For most application areas, I still feel that's true.

(Here's a challenge: How many 3D-printed end-use products are in the room or space you are currently in? (I rest my case.))

This is why we felt that Kickstarter was the perfect platform to launch COR Zero on. We can now help individual innovators, designers, and engineers make their ideas real.

I was thinking about ending this article with "4000 days late is better than never".

But COR Zero isn't late. It is right on time.

The COR Zero Kickstarter launches today, and runs until November 7th. We hope you'll consider supporting us on this journey.

*Wevolver receives an affiliate commission for any purchases made by you on the affiliate website using this link. Read more about Wevolver’s policy for affiliate links.