Understanding RF Applications: Communication, Sensing, Power Transfer and Beyond

Article #6 of Mastering RF Engineering: RF technology powers everything from Wi-Fi and Bluetooth to radar, sensing, geolocation, and directed energy systems. This article explores the most essential RF applications, how they work, and their growing impact on modern technology and infrastructure.

This is the sixth article in our multi-part series on “Mastering RF Engineering,” brought to you by Mouser Electronics. The series explores how RF technology is designed, built, and tested, highlighting the principles, components, and applications that make modern wireless systems possible. Each installment introduces a new dimension of RF engineering, giving readers a structured path from fundamentals to advanced practice.

Articles from this series:

- An Introduction to RF Theory, Practices, and Components

- Understanding RF Signal Chains: Key Building Blocks and Components

- How to Specify an RF Antenna: RF Antenna Operation, Design, Selection, Testing, & Verification

- Understanding RF Circuit Fabrication and Interconnects

- Digital RF Technology Explained: How Digital Signal Processing is Revolutionizing Wireless Systems

- Understanding RF Applications: Communication, Sensing, Power Transfer and Beyond

- The Fundamentals of RF Testing and Measurement Techniques

Radio frequency (RF) technology is increasingly used to connect, sense, and remotely power devices as part of an ongoing shift in human technology toward converting existing mechanical, pneumatic, and hydraulic systems to electrical and electronic systems. RF technology is affecting nearly all modern transportation, personal communication, utilities, robotics, automation, enterprise facilities, logistics, and facilities management activities. Future predictions of human civilization include cities, industrial facilities, and agricultural installations where virtually every machine is wirelessly connected and coordinated by advanced artificial intelligence (AI) systems.

This article explores the most common and significant current RF technologies and describes how they work at a high level, with a particular focus on wireless communications. Other topics covered include radar, radio navigation, RF imaging, RF materials characterization, wireless power transfer, and energy harvesting.

RF Wireless Communication

Wireless communication is the use of transmitted and received signals passing through an unguided medium, such as free space or open air, without the use of a physical conductor. Wireless communications can be performed using audio signals, ultrasonic signals, vibrations, infrared (IR) light, visible light, or other methods, but presently, the most common implementation for wireless communications is RF technology. Some of the preeminence of RF technology is the legacy of early radio and how it changed human life. More importantly, that legacy sparked investment and research into RF technologies, leading to the incredible capabilities of modern RF wireless communication systems.

The rise of cellular phones and the internet helped drive the widespread adoption of Internet of Things (IoT) technology. These new use cases led to the development and growth of different wireless communication standards and protocols. The mass use of new IoT technologies and wireless communications has also spawned a host of security concerns and new technologies to improve the safety of communications and control through wireless systems.

Common Wireless Communication Standards & Protocols

For RF systems of the same type to efficiently and effectively exchange information so that digital data within the signals can be embedded and extracted from those signals, the RF systems need to have compatible protocols. A wireless communication protocol is a standardized set of specifications and procedures that dictates how wireless communication devices exchange signals and information. These protocols are defined by standards organizations that develop and maintain the protocols.

These standards bodies are generally industry consortia, but there are also international government-funded organizations that cover RF technologies and host some protocols. These cover very detailed operations for wireless devices that meet the certification requirements for the protocol to intercommunicate at an acceptable level of reliability (Table 1). Many wireless protocols evolve, and new versions that take advantage of new technology and methods are proposed and eventually incorporated into a standard. This process can take a few years, as industry support is often required to pair hardware and software along with the new protocol for it to succeed.

Table 1: Common wireless communication standards, protocols, and their technical characteristics

Wireless Communication Standards & Protocols | Standards Body | General Use | Digital/Analog Modulation | Radio Technology |

Wi-Fi | IEEE 802.11 | Wireless LAN | OFDM, OFDMA | MIMO, MU-MIMO, DSSS |

Cellular Wireless (2G, 3G, 4G LTE, 5G) | 3GPP | Mobile internet | OFDMA, TDMA, SC-FDMA | MIMO, MU-MIMO, FDD, TDD |

NFC | NFC Forum | Contactless payment, access control, authentication, provisioning | Modified Miller, ASK | |

RFID | ISO 14443 and ISO/IEC 18000 | Access control, authentication, provisioning | AM, FM, ASK, OOK | |

Bluetooth® | Bluetooth SIG | P2P, PAN data stream, & IoT provisioning | GFSK, PSK, pi/4-DQPSK, 8-DQPSK | FHSS |

Zigbee | CSA | P2P, PAN, mesh networks, & IoT | OQPSK, BPSK | DSSS |

Z-Wave | Z-Wave Alliance | P2P & mesh network IoT | OQPSK, BPSK | DSSS |

LoRa-LoRaWAN | ITU | Low-power WAN for IoT, machine-type communications | CSS | CSS |

NB-IoT | 3GPP | Low-power WAN for IoT, machine-type communications | OFDM, SC-FDMA | FD, HD, FDD, TDD |

LTE-M | 3GPP | Low-power WAN for IoT, machine-type communications | QPSK, 16-QAM, 64-QAM | FD, HD, FDD, TDD |

Ultra-wideband (UWB) | IEEE 802.15.4z | Impulse radio, location, car connectivity | PPM, BPSK, BPM | Radar |

Top Wireless Communication Applications and Use Cases

For many people, the most common wireless communication technologies they encounter daily are cellular telecommunications and wireless local area network (WLAN) technologies, mainly Wi-Fi. Bluetooth is common for connecting personal electronic devices, such as smartphones, automobiles, wireless audio headsets, and wireless speakers, and for provisioning IoT devices.

Contactless payment using near-field communication (NFC) is growing in popularity, while RF identification (RFID) is increasingly being used for access control to buildings, hotels, storage, and equipment. Zigbee and Z-Wave have carved out a significant portion of the smart home networking market, but are also used in enterprise and mesh networking applications. LoRaWAN is being used for low-distance and low-power communication for IoT devices, such as smart city applications, industrial monitoring, and asset tracking.

Narrowband IoT (NB-IoT) and LTE-M are machine-type communications protocols designed for a multitude of IoT devices connecting to cellular systems. UWB is a revitalization of an older standard that is now being used as a short-range burst communication and high-precision location and proximity systems, such as car key fobs and vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communications.

The core of these wireless communication devices is typically a wireless communication chipset that allows for programmability and reconfigurability, or a dedicated chipset for a given wireless protocol. Some wireless communication chipset manufacturers make multiprotocol chips capable of using two or more protocols, such as the Silicon Labs Wireless Gecko multiprotocol family of system-on-chips (SoCs), which are ideal for low-power IoT connectivity applications. More on these advanced SoC platforms is discussed later in this article.

Wireless Security

With more people and enterprise, industrial, and government systems using wireless communication technology, wireless security is an area of increased focus for wireless system developers. All devices with wireless networking technologies can be remotely accessed and infiltrated, a process known as hacking. Hacking a wireless device can lead to more than just compromised information or control capability of the device; a wireless device can also be used as a vector to access other devices on a wireless network (known as network injection). Moreover, if the hacked devices are connected to a larger network or the internet, those devices can be used to attack or infiltrate other systems in other networks. Even a simple IoT sensor on a wide-area network (WAN) can be used to compromise an entire network, and a simple device like an IoT sensor wireless interface can be used as a hacking device if properly reprogrammed. More sophisticated wireless hacking tools exist, such as software-defined radio (SDR) devices that can be modified via hardware, software, and/or firmware to allow for the use of hacking tools.

As a result, information technology (IT) organizations have made substantial efforts to prevent unauthorized access by enhancing the security of active wireless devices and systems, especially during provisioning. These organizations use a variety of wireless intrusion prevention systems (WIPS) or wireless intrusion detection systems (WIDS) to monitor and defend against unauthorized wireless hacking for enterprises, industrial, and government networks (Table 2).

Table 2. Layered defense examples for a wireless network Source: NASA; recreated by Mouser Electronics[1]

Class of Attack | First Line of Defense | Second Line of Defense | Defense Mechanisms Deployed |

1. Passive | Link & network layer encryptions and traffic flow security | Security-enabled applications | NAT translation, Telnet, virtual private network |

2. Active | Defend the enclave boundaries | Defend the computing environment | Firewalls, routers |

3. Insider | Physical & personal security | Authenticated access controls, audit | Passwords, smart card readers, audit & security logs |

4. Close-In | Physical & personal security | Technical surveillance countermeasures | Security cameras, biometric scanners, keypad smart locks |

5. Distribution | Trusted software development & distribution | Run-time integrity controls | Apply all the latest updates to operating systems, applications, anti-virus signatures, spyware signatures |

A basic aspect of wireless security is encrypting one-way or two-way communications. Not all encryption methods are created equally, and wireless sniffers can capture wireless signals and decode them if the encryption method used isn't adequately robust. This is why every newer generation of Wi-Fi uses a more advanced encryption method to increase the challenge and resources needed to crack the wireless communications encryption.

Some networks also use restrictions on devices, such as Media Access Control (MAC) address filtering and other approaches, to prevent unauthorized access to a network. There are various methods to defeat this approach, some of which use the credentials of authorized network devices obtained via MAC spoofing, "cafe latte" attacks, man-in-the-middle attacks, or other wireless network spoofing methods. Some wireless networks are protected physically by using RF shielding to prevent unauthorized devices or any devices outside of a controlled area from receiving adequate signal reception.

With physical access to a wireless device, which could be anything from a laptop to an IoT sensor, it is often possible to hack the device and obtain credentials adequate to launch an attack. This is why many chip manufacturers of IoT devices are now including on-chip security measures that raise the difficulty of accessing memory and operating the device outside of intended parameters. Security is also an area where counterfeit chips have become an issue, with many chip makers and device manufacturers investing heavily in methods to prevent counterfeit chips from being built into new designs. Some of these methods include dedicated provisioning services that aren't accessible without protected hardware features.

Geolocation, Navigation, and Timing

Geolocation services are one of the most used wireless services around the globe for applications such as personal travel, transportation, aviation, and surveying. The most common method of geolocation is using Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), such as Galileo (European Union), GPS (USA), GLONASS (Russia), QZSS (Japan), IRNSS (India), and BeiDou (China). These systems use satellite networks in the Earth's orbit that constantly transmit ranging and timing data accessible by GNSS-enabled receivers. These receivers are also equipped with circuits that can compare the timing and ranging data from several satellites to compute the exact position of the GNSS receiver relative to the satellite constellation. By storing and comparing multiple GNSS receiver measurements, it is possible to estimate the direction and velocity of travel.

Radar

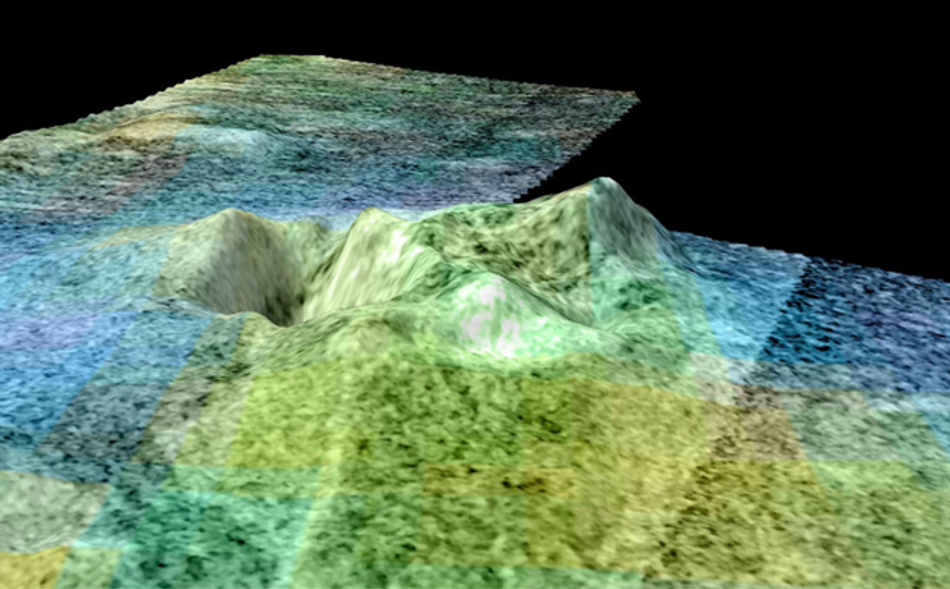

Radar is an older RF use case that continues to evolve and be implemented in new ways. It uses the dynamics of RF signal reflections (known as backscatter) from a radar transmitter to gather information about the environment and targets. Readings from tracking radar can decipher information about a radar target, such as its size, direction, velocity, and other characteristics. Many other types of radar, such as weather radar and synthetic aperture radar (SAR), are used to map and capture information precisely about the composition of target land surfaces (Figure 2).

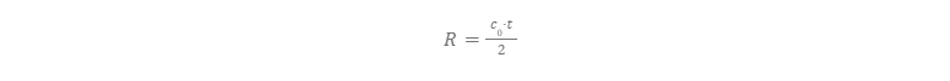

To achieve these readings, the radar must be able to measure the difference in time between when a radar signal is transmitted and when the backscatter signals are received. This measurement is derived from the following formula:

In this formula, R is the slant range from the antenna to the target, c0 is the speed of light, and t is the measured run-time. Information about the surface that caused the radar reflections can be determined based on more advanced signal characteristics. Using studies of how RF signals interact with different materials, one can determine the condition of the objects being illuminated by a radar with the appropriate technology.

For instance, a weather radar can be used to determine the amount of water vapor density in the clouds, and radar used in grain silos can determine the depth of the grain as well as the moisture content. AI and machine learning (ML) technologies make it possible to infer even more information from radar targets. Researchers are using these tools for space exploration to map distant celestial bodies and discover ancient human occupation sites and buildings previously hidden by dense foliage or complex landscape features.

RF-Based Imaging and Sensing

Beyond radar, RF signals can also be used similarly to visual and IR for imaging. Because RF signals interact with visual and IR light differently than with physical objects, RF imaging technologies can be used for unique use cases. RF imaging technologies also use different methods of capturing electromagnetic energy than typical cameras do, using compact antenna array designs instead of photocapture cells.

Depending on the frequency at which the RF imager operates, the RF signals captured may more efficiently pass through foggy, dusty, snowy, or otherwise visually occluded environments, making them ideal for rugged and hazardous conditions, such as storms. A more recent application of RF imaging is millimeter-wave imaging technology, which is used in security scanning systems to detect concealed objects under clothing by analyzing RF energy reflections, rather than visually seeing through clothing.

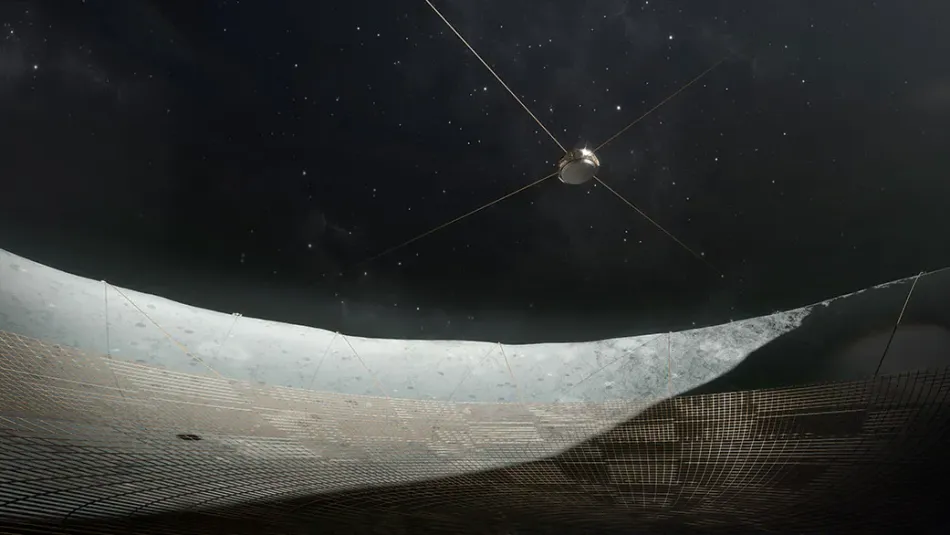

A radio telescope is a type of RF imaging that passively captures radio signals from outer space for scientific study. A possible future US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) mission is the Lunar Crater Radio Telescope (LCRT), a proposed radio telescope constructed of wire mesh and installed inside a crater on Earth's moon (Figure 3). Radio telescopes allow operators to measure radio signals that are otherwise invisible to other types of telescopes, and these signals may be the key to learning about aspects of the ancient universe and other astronomical phenomena.

RF Material Characterization

As RF signals pass through or by materials, the signals are altered. Moreover, placing materials with certain dielectric, conductive, semiconductive, and magnetic properties near exposed waveguides, transmission lines, or resonant cavities leaves indelible marks on reflected signals. These changes to RF signals passing through materials and reflected from them can be used to perform measurements if the setup is adequately controlled and calibrated. The key measurements using RF signals are complex dielectric permittivity, complex magnetic permeability, conductivity, and resistivity. With non-contact material measurement methods, RF material characterization apparatuses can be used on extremely cold or hot materials and under a variety of other conditions.

These RF material measurements can also be performed on gases and liquids as they flow past a measurement surface or when they are contained in sample containers. Such means can also detect the densities of gases and liquids, as well as other important features of non-solid materials, such as the composition of gases.

A common use of RF materials measurements is to test the conformity of materials, such as radomes and aerospace materials. Specifically, RF materials measurements can be used to detect gaps or nonuniformities in a materials matrix, such as imperfections in aerospace composites. Other notable uses of RF materials measurements are detecting soil properties, uses in medical studies, such as that of neurological cell tissue, chemical composition testing, and during manufacturing for quality control of printed circuit board laminates.

Wireless Power Transfer and Energy Harvesting

Wireless power transfer (WPT) includes techniques such as inductive coupling, capacitive coupling, and RF-based transmission. These techniques enable the transfer of electrical energy without physical connectors. While inductive and capacitive systems are typically used for short-range charging, RF-based energy transmission enables longer-distance power delivery.

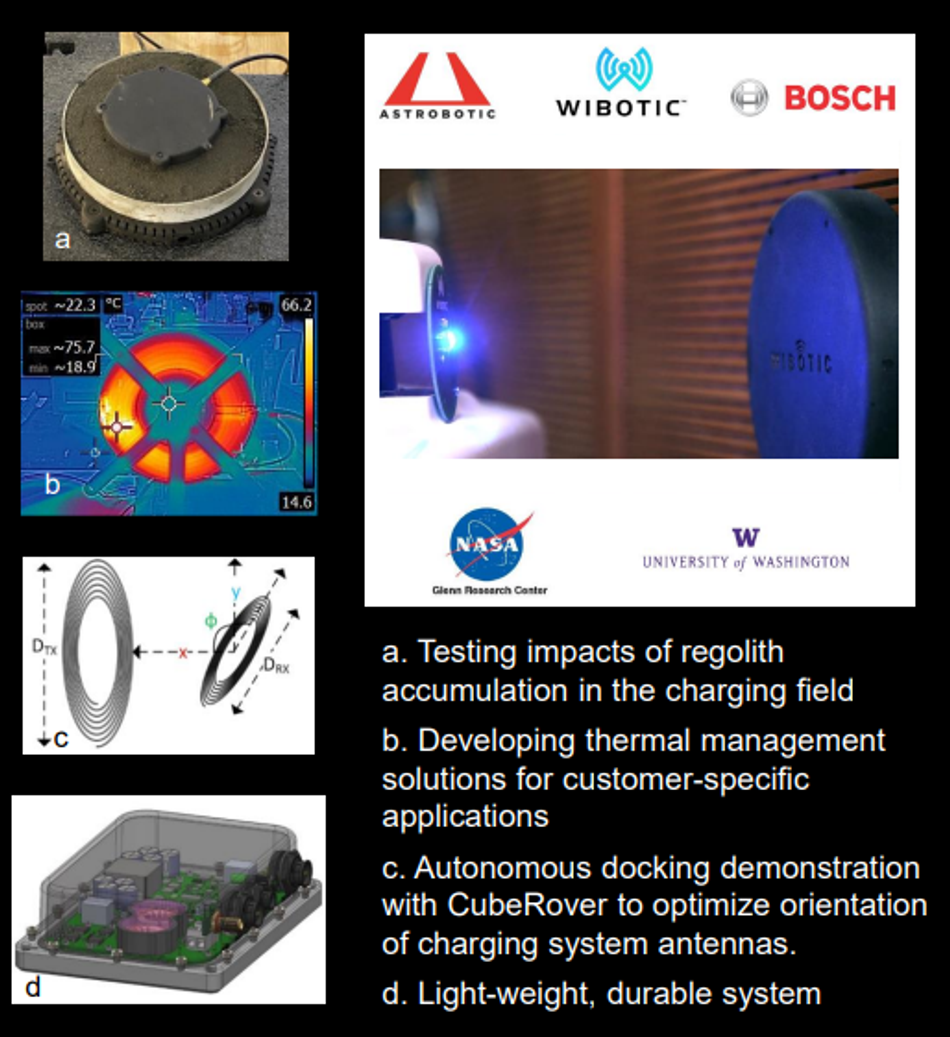

Although RF-based WPT is less efficient than guided systems, it can be improved through technologies such as resonant antennas, beamforming, and beam steering, which focus and direct energy toward specific receivers. A simple and relatively common WPT method is the use of contactless charging, such as inductive charging. These methods are already used in everyday applications like wireless charging for smartphones and wearables, and are now emerging in electric vehicle charging and industrial automation. NASA is even researching wireless power transfer through its Ultra-Fast Proximity Charging (UFPC) project, which aims to develop contactless charging systems for small devices operating on the moon (Figure 4).

With the modern abundance of RF signals used for communication and sensing in most environments, it is possible to harvest energy passively from ambient RF signals. This enables completely wireless and battery-free operation for certain sensors, reducing the need for maintenance or wired infrastructure.

High-power RF transmission also has important implications in areas such as system interference testing, RF exposure research, and electromagnetic resilience engineering. Technologies originally developed for long-range RF power transmission, such as phased array antennas, are now being evaluated for their potential in controlled applications like signal jamming, RF interference management, and electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) testing. These RF applications are particularly relevant in critical infrastructure and defense-related research, where understanding and controlling electromagnetic environments are essential.

Wireless Connectivity Solutions from Silicon Labs and Mouser Electronics

As wireless connectivity grows across the industry, designers increasingly rely on high-performance, energy-efficient RF solutions that simplify development without compromising range or reliability.

Silicon Labs’ wireless SoCs and companion development boards deliver precisely that, offering exceptional RF performance, robust security, and low-power operation in compact, production-ready platforms. Together, these solutions help accelerate wireless designs for smart devices, wearables, sensors, and connected infrastructure.

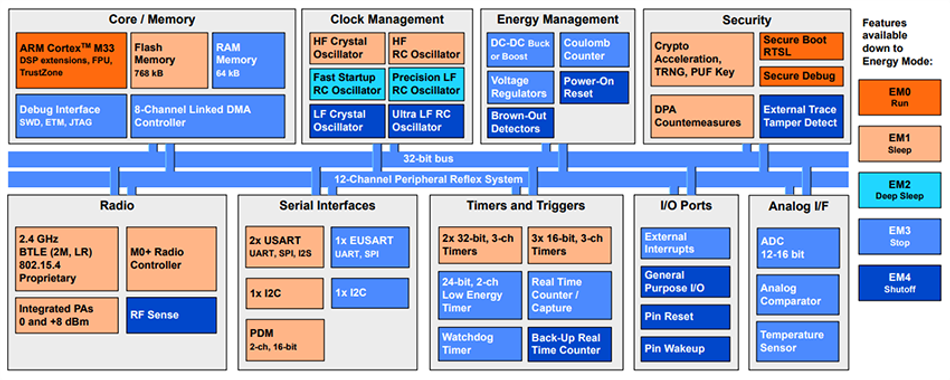

Silicon Labs EFR32xG29 Series 2 Wireless SoCs

The Silicon Labs EFR32xG29 Series 2 Wireless SoCs are powered by a 76.8MHz Arm® Cortex®-M33 processor with DSP and floating-point support, delivering strong processing performance for real-time wireless applications. The family includes both EFR32BG29, the Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) variant, and EFR32MG29, the multiprotocol variant, allowing designers to select the most suitable wireless capability while using a common hardware and software platform.

The SoCs combine excellent radio sensitivity, long-range connectivity, and ultra-low energy operation ideal for battery-powered systems. The SoCs are enhanced by Secure Vault™ High security and Arm® TrustZone® isolation, providing a robust, and scalable platform for next-generation IoT, healthcare, and industrial devices that demand performance, efficiency, and trust.

Specification | Description |

Core | 76.8MHz Arm® Cortex®-M33 with DSP & FPU |

Memory | 1024KB Flash, 256KB RAM |

Radio | 2.4GHz wireless radio (BLE/Zigbee®/Thread/proprietary) |

TX Power | Up to +20dBm (EFR32BG29) and Up to +8dBm (EFR32MG29) |

RX Sensitivity | –106.8dBm @ 125kbps GFSK |

Power Efficiency | 3.6mA RX @ 1Mbps, 4mA TX @ 0dBm |

Security | Secure Vault™ High, Arm® TrustZone®, Secure boot |

Deep Sleep Current | 0.16µA (EM4 mode) |

Package Options | QFN40 (5×5mm, EFR32BG29 and EFR32MG29), WLCSP45 (2.8×2.6mm, EFR32BG29) |

Applications | IoT sensors, medical devices, smart home, industrial automation, wearables |

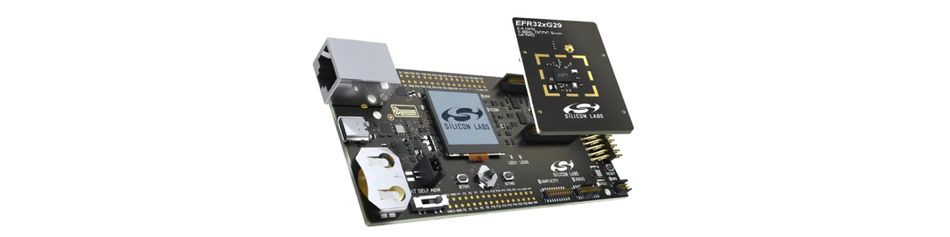

Silicon Labs ERF32BG29 & ERF32MG29 Development Boards

The Silicon Labs ERF32BG29 and ERF32MG29 Development Boards offer a complete environment for testing and developing next-generation Bluetooth® and multiprotocol wireless applications. Each board integrates an EFR32xG29 Gecko Wireless SoC and connects to either a Wireless Starter Kit or the enhanced Wireless Pro Kit mainboard.

Developers can monitor energy usage in real time through the Advanced Energy Monitor (AEM), debug applications with the integrated debugger, and analyze packet-level performance using the Packet Trace Interface (PTI). Additional features such as a virtual COM port, onboard sensors, and a 20-pin EXP header simplify system evaluation and prototyping.

The development boards are available in BRD4412A, BRD4413A, and BRD4420A variants, supporting applications from industrial automation and smart lighting to wearable and battery-powered IoT devices.

Conclusion

RF technology is used for an incredibly diverse range of applications. Modern technology's ability to control, direct, capture, and process RF signals allows for ultra-fast and reliable communication, advanced imaging, precise sensing, and material measurement. As RF applications continue to expand, so do challenges around signal integrity, interference, and system-level security. Protecting these increasingly complex RF networks from threats like jamming, spoofing, and unauthorized access is becoming just as important as the innovation driving them forward.

Most people around the world rely daily on wireless communication and sensing applications, such as weather radar. This expanded use of RF technology is only beginning. Smartphone technology popularized cellular communications and wireless internet less than 20 years ago, and the future will likely continue to be transformed by RF innovations made today.

References

[1] Scotti V Jr. Computer network security: The challenges of securing a computer network. NASA USRP Internship Final Report. Brevard Community College; 2011. Available from: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20110014451/downloads/20110014451.pdf

[2] NASA. Cassini Orbiter: RADAR Instrument. NASA Science Mission Directorate. Available from: https://science.nasa.gov/mission/cassini/spacecraft/cassini-orbiter/radio-detection-and-ranging/

[3] Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Lunar Crater Radio Telescope: Illuminating the Cosmic Dark Ages. NASA; 2021 May 5. Available from: https://www.nasa.gov/solar-system/lunar-crater-radio-telescope-illuminating-the-cosmic-dark-ages/

[4] Eckard J, DeMinico M. Ultra-Fast Proximity Charging (UFPC) – TP. NASA Technical Poster; 2021. Available from: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20210021025/downloads/UFPC-TP%20-%20APR%20Poster.pdf

This article was originally published by Mouser Electronics. It has been edited by the Wevolver team and Ravi Y Rao for publication on Wevolver. Upcoming articles in this series will continue to explore key areas of RF engineering, offering engineers practical insights into the design and implementation of modern RF systems.