Robots and Religion: Mediating the Divine.

As icons and rituals adapt to newer technologies, the rise of robotics and AI can change the way we practice and experience spirituality.

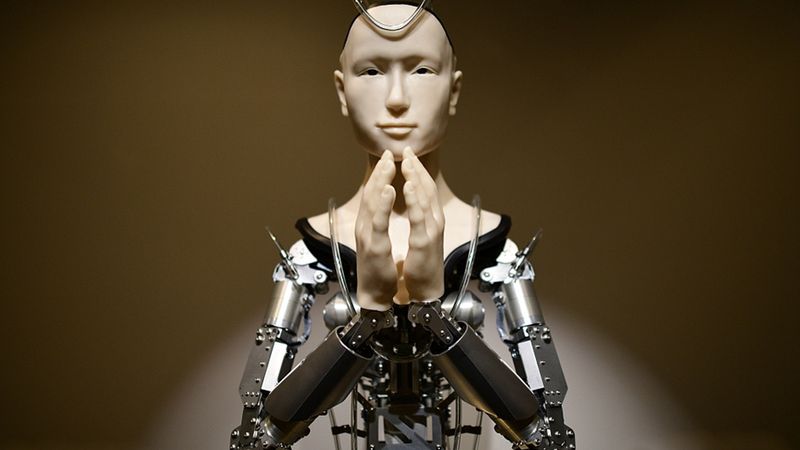

The android called Kannon Mindar. Photo by Richard Atrero de Guzman

Some 100,000 years ago, fifteen people, eight of them children, were buried on the flank of Mount Precipice, just outside the southern edge of Nazareth in today’s Israel. One of the boys still held the antlers of a large red deer clasped to his chest, while a teenager lay next to a necklace of seashells painted with ochre and brought from the Mediterranean Sea shore 35 km away. The bodies of Qafzeh are some of the earliest evidence we have of grave offerings, possibly associated with religious practice.

Although some type of belief has likely accompanied us from the beginning, it’s not until 50,000–13,000 BCE that we see clear religious ideas take shape in paintings, offerings, and objects. This is a period filled with Venus figurines, statuettes made of stone, bone, ivory and clay, portraying women with small heads, wide hips, and exaggerated breasts. It is also the home of the beautiful lion man, carved out of mammoth ivory with a flint stone knife and the oldest-known zoomorphic (animal-shaped) sculpture in the world.

We’ve unearthed such representations of primordial gods, likely our first religious icons, all across Europe and as far as Siberia, and although we’ll never be able to ask their creators why they made them, we somehow still feel a connection with the stories they were trying to tell.

Left: The Venus of Dolní Věstonice (29,000 BCE — 25,000 BCE). Right: The Lion-man of the Hohlenstein-Stadel, between 35,000 and 40,000 years old. Source: Wikipedia. CC.

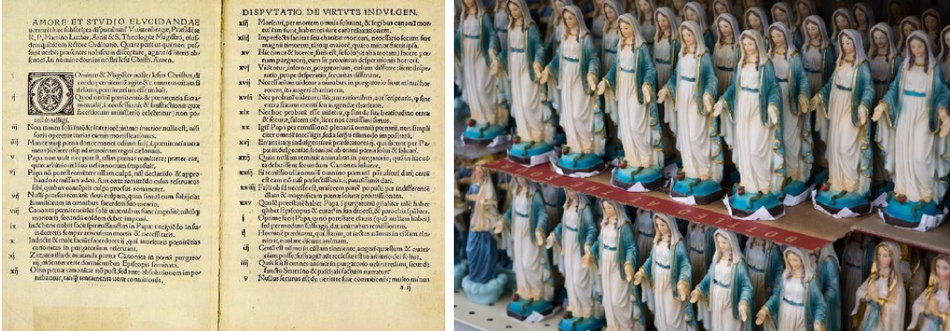

We know that the spiritual foundations of humanity upon which we subsist today (Monotheism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism) were laid independently and simultaneously around 900 to 200 BCE, while the Middle Ages established present-day world religions throughout Eurasia. As history does, things moved fast from there. Eventually, water-powered paper mills replaced the laborious handcraft of Chinese and Muslim paper-making, while the printing press allowed for religious texts to spread rapidly, capturing the masses in the Reformation and breaking the monopoly of the literate elite.

In 1560, King Philip II of Spain commissioned Juanelo Turriano, a clockmaker who specialized in movable figurative sculptures, a machine of prayer to beg God to save his child from a deathly illness. “A miracle for a miracle,” he promised. Turriano was in charge of creating the earthly one that would pay for the second. He came up with the mechanical monk, a marvel of early automation. Its body can perform a variety of impressive actions, from moving his head, mouth, and eyes, beating his chest with his right arm and raising his left to lower the cross and rosary. What I find personally fascinating is that, even though the monk’s mechanisms were hidden beneath his cloak, some of the components were decoratively shaped. Away from human eyes but not from those of the divine.

“[The mechanical monk] may have been created as an act of religious gratitude, but it stands (and walks and prays) as a tribute to human ability.” Lauren Davis, Gizmodo.

Turriano’s masterpiece doesn’t see a conflict between mechanics and art, automation and spirituality. It shows us, instead, a possibility.

Even with the Industrial Revolution replacing most of the meticulous processes of carving and painting, allowing us to mass-produce objects (and icons) with little need for human intermediaries, it’s our drive that determines the direction of our creations. And we do the same with our rituals as we do with our icons.

Mass communication now enables ceremonies and observances to be streamed on TV and online while messages of faith are spread via Twitter, making us question the way we practice religion and experience spirituality but also facilitating our access to them, especially for those who cannot leave their homes or travel to certain places.

Robots have always raised questions about divine creation and fears of dehumanization, transhumanism and even extinction. But they can also be perceived as intermediaries with the divine.

What does this mean for the development of AI? As automation permeates our lives, more and more every day, the question is not whether robotics and religion can co-exist. It’s how we can make both collaborate with each other in order to allow technology to help us become better, more connected people.

Left: Martin Luther’s 95 Theses which sparked off the Reformation. In only two years, Luther’s tracts were distributed in 300,000 printed copies throughout Germany and Europe. Wikipedia, CC. Right: Virgin Mary figurines for sale in San Francisco, California. Courtesy of Thom Masat, CC.

In this article, we’ll explore our practices in the context of the latest advances in robotics, their design and some interesting examples of theomorphic robots.

Introducing Theomorphic Robots

If we look at the field of social robotics, we can see that most robots have been previously classified into three main categories based on the way they look (Dingjung Li et al.):

- Anthropomorphic: Robots with human and humanoid features, usually considered good for public assistance, business, research and healthcare;

- Zoomorphic: Robots that resemble animals, used more successfully in security, research, healthcare, education and entertainment; and

- Functional: Robots with a functional appearance designed according to their specific purpose and more appropriate for security and public assistance.

Gabriele Trovato, a researcher from Waseda University interested in exploring robotics in the context of religion, argues that this classification is incomplete because it doesn’t encompass the cases that fall between the three categories, nor does it account for robots inspired by plants and nature.

The anthropomorphic robot RoboThespian, the zoomorphic Paro and the functional ARC Mate. Wikipedia, CC.

His more exhaustive classification incorporates, instead, groups like partially anthropomorphic, ideomorphic, biomorphic and physiomorphic, which are based on the general categories of divine representation linked to human religion, such as gods/holy humans, sacred objects, animals and symbols and sacred nature.

More importantly, Trovato introduces the concept of theomorphic robots — representations or conceptions of something or someone in the form of deity.

Differences in Religions and their Effects on Robotics

What a theomorphic robot will look like will vary depending on the specific religion and the connotations that a particular deity has. Let’s explore some of these distinctions.

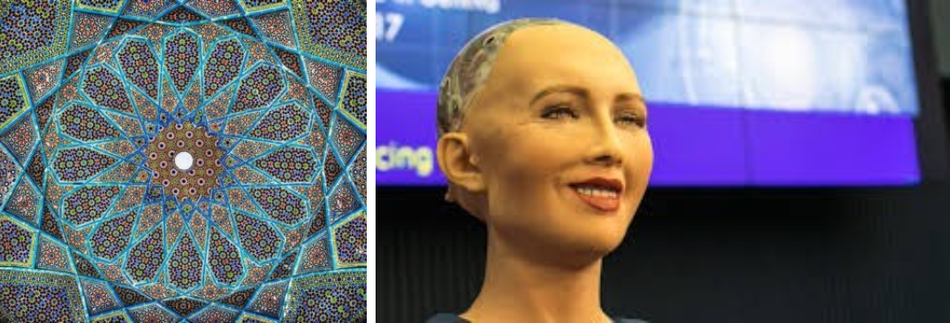

In Islam exists an anti-iconic doctrine of prohibition of symbols and religion icons. Hence the depiction of any living beings (animal or human) has been avoided, an influencing factor on the attitude of people of such countries towards humanoid robots. At the same time, the nature of Islamic faith, which requires rituals to be performed on daily (prayer), yearly (Ramadan) and once in a lifetime basis (pilgrimage to Mecca), also raises questions about the physical presence in a ritual. A robot could help those who are physically impaired and cannot perform them, and robotic initiatives such as the androids Sophia (granted citizenship in Saudi Arabia) and IbnSina (the world’s first robot with Arabic language conversational abilities) show an openness to these initiatives and their potential benefits.

Hinduism conceives God as a multiplicity and accepts different ways of worship. Texts such as Bhagavata Purana and Ramayana from the Vedic civilization in ancient India reference advanced technology; in Yoga Vasishta it’s mentioned that an Asura (a class of divine being) named Sambarasura created three “war machine” robots called Dama, Vyala and Kata to defeat the Adityas, while in modern India we begin to see efforts to include automatization and robotics as a means of cultural diffusion.

Judaism gives us the Golem, a man-made creature built from clay or mud and an example of man’s arrogance in molding a living creature. Yet the act of building a golem is itself a prayer, as it deconstructs the mystery of what it means to be human while, at the same time, Orthodox families use a wide range of objects to automatize tasks and enhance the Sabbath experience.

Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism and Shinto share come commonalities when it comes to the dualism of mind and body. Buddhism has spread through southern China and Sri Lanka using shadow puppets and images of gods and goddesses with moving hands, while Japan’s unique relationship with the inanimate (Confucianism ascribes souls to all living and non-living objects) allowed Masahiro Mori to state that “robots have the Buddha-nature within them” and “the potential for attaining Buddhahood”.

Finally, Christian theology is generally seen as keeping an opposing stance towards technology, arguing that its considerable momentum could lead to alienation of man from himself and nature. However, through the Middle Ages and later, automata brought to life Biblical passages through the use of mechanical angels and fire-breathing devils.

Acceptance of Theomorphic Robots

Trovato argues that theomorphic robots might be accepted more favorably because divine representations are familiar to both believers and non-believers.

Theomorphic robots can be perceived as giving us protection through divine or supernatural abilities. They can also be perceived as sacred, in the same way as a copy of the Quran is held in high regard compared to a common book.

Elderly people can benefit from the advances of robotics in terms of healthcare and connection to loved ones (telepresence robotic systems have been proven to support and foster social participation) and might take advantage of robotic versions of familiar objects if they are more emotionally attached to religion.

Robots can use as educational tools for children, with artificial intelligence showing this area has the biggest potential to make a positive impact, while illiterate people, aware of local traditions and folklore, seem to show a greater suspension of disbelief in human–robot interaction as exemplified by an intense reaction to stimuli in this study.

Robots possess unique capabilities which could give them an advantage over human personnel in specific contexts (for example they have endless patience and be constantly available), however, they also reduce the possibility of human contact.

Designing Religious Robots

When we design religious robots, we cannot use efficiency as a correct measure of technology success. Trovato proposes that we instead use perceived sacredness, which is inevitably intertwined with our universal psychological needs of relatedness, autonomy, and competence.

Now, perceived sacredness is highly subjective; it depends on the faith of the person, their degree of religiosity/spirituality and their tendency to need a physical object to support their beliefs. The general agreement leans towards less visible robotic elements as a way to appear like a credible representation of the divine. Below are some other principles that might prove useful.

Skeuomorphism

Skeuomorphism (using real-world references and metaphors) is already an essential component for the symbols and icons of most religions — such as the stone crosses in Scotland that represent a wooden cross. If an object is designed to retain features of another already existing and familiar object or icon, its acceptance can be improved as it makes affordances stronger. It’s therefore critical that the robot follows conventions in sacred art.

Materials

The materials used to create the robots are also an important element to consider. Precious metals linked to a sacred place or relic can have extraordinary value for a believer. Gold, due to its indestructible nature, malleability and relative scarcity, has traditionally been considered an ideal material to embody divine qualities. Certain alloys, like the composition of bronze in statues, can also have a symbolic value attached to them, and the ways in which objects are fabricated — for example, while reciting an appropriate prayer — can also hold particular meaning.

Light

The use of light can become advantageous as they have been more traditionally associated with the divine presence, in contrast with darkness as part of a good-evil dualism, familiar both in popular culture and sacred art. Many religious celebrations and rituals utilize light, and so do funeral processions and prayer ceremonies. It’s also not rare to find, nowadays, automation of the act of lighting candles in a Church (the candle rack is replaced by LED candles in a coin-operated machine) to support meditative thought, express support for others and help to remember the deceased.

Interaction

In terms of human-like response when it comes to movement and interaction, excessive communication abilities can take away the suspension of disbelief and turn the robot into a mere product or toy. Like any other existing sacred object, religious robots should act as an intermediary with the divine, rather than impersonate a deity. A robot is still a tool on which the divine is projected — reason why religious authorities can also provide additional legitimacy to them by conferring the sacredness or the holiness through a ritual.

Examples of Religious Robots

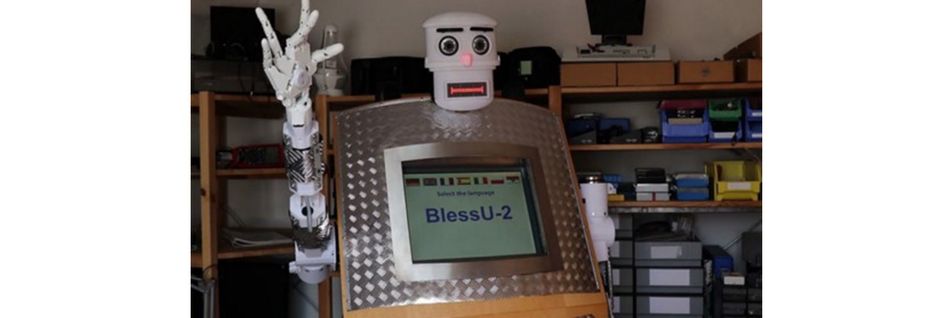

We’ll revise three religious robots that have recently been tested. DarumaTO-2 and SanTO are theomorphic robots, while BlessU-2 is an anthropomorphic robot that can give blessings.

DarumaTO-2

(Partially anthropomorphic, theomorphic)

Darumas are widespread Japanese dolls said to bring good luck in a variety of occasions. They are modeled after Bodhidharma and work in the following way: They start with both eyes white (or closed). You paint the right eye black when you fix a goal, and the left one when you accomplish it (so now both eyes are open).

DarumaTO-2 is the second prototype for a robotic version of a Daruma. Because these are popular among the older generations, they can be particularly useful for nursery homes; they are limited (and accessible) in their range of interaction, and their appearance is familiar and not distressing like it could happen with a zoomorphic or anthropomorphic robot.

Preliminary investigations show that elderly people seem to be comfortable with the idea of a “talking Daruma” — that is, as long as the word robot is not mentioned. DarumaTO-2 is a socially assistive device that can help with the problem of aging societies through its familiar appearance.

SanTO

(Partially anthropomorphic, theomorphic)

SanTO (pictured above) was created as a prayer companion for Catholics. It has the shape of a statue of Christ, with several skeuomorphic and communication elements included in its design (the posture of the arms, the presence of the cross, the use of touch, light and voice reverb).

The robot contains a database of prayers and can give answers based on sacred texts. SanTO can also be a good use case for the elderly, although it’s in Latinamerica where familiarity with personal altars for saints can make it a good house companion. By incorporating cultural touchstones such as religious features, SanTO can make users feel comfortable with the technology.

“Religion has evolved through history, from oral tradition to written tradition to press and mass media. So it’s very reasonable to think that AI and robotics will help religion to spread out more.” Gabriele Trovato.

BlessU2

(Anthropomorphic, non-theomorphic)

The blessing robot BlessU2 is a humanoid robot designed by the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau in Germany to deliver blessings. It measures 1.80 meters high and has a touch screen in its chest, movable arms, eyeballs, and eyebrows. It also speaks seven languages in a male or female voice.

BlessU2 interacted with more than 10,000 visitors of a public exhibition, offering a choice of four types of blessings (and randomly picking one of ten bible verses for each): traditional, companionship, encouragement and renewal. After raising its arms, its palms flashing lights as it recites the passages, the robot offers a printout of its blessing.

BlessU2 was considered more of an experiment to inspire discussion about the future of the Church in a digitalized world. And it did. After all, what’s the meaning of a blessing and who can give them? What’s the specific human component in it, and can God give blessings through technology? Half of the comments BlessU2 received were positive (51%), one-third was neutral (29%) and one-fifth was negative (20%). Positive comments mentioned anthropomorphic features of the robot, such as hand gestures and use of light, while negative feedback had to do more with the details that mimicked a human priest, the non-responsiveness of the gaze and face, and the choice of materials.

Conclusions

Robots are a statement to human creativity and can offer invaluable assistance and open up new possibilities for some groups of people; for example, those whose physical condition is limited due to age, injury or sickness.

They can also alter, expand, enhance and transform our religious dimension, but the experience can also be easily ruined when the makers of technology do not understand what constitutes a meaningful interaction. Many religious activities have an overabundance of meaning that doesn’t always benefit from the simple, functional end of certain technological advances. It’s not difficult to render a ritual profane this way.

As our societies change rapidly and become more dependent on new technologies and what they can do, it’s inevitable to wonder if innovation can actually allow a new form of religion and myth to emerge.

Religious robots are not supposed to replace face-to-face human encounters but act as support to facilitate access for those who require it. Religion and spirituality have always been, in part, medially communicated. Robots are just another kind of medium, one fueled by the possibilities of artificial intelligence, machine learning and automation.

Referenced works:

- G. Trovato et al.: “Religion and robots: towards the synthesis of two extremes”, International Journal of Social Robotics, p. 1–18, May 2019

- D. Löffler: Blessing Robot BlessU2: A Discursive Design Study to Understand the Implications of Social Robots in Religious Contexts.International Journal of Social Robotics, May 2019

- D. Li, P.L.P. Rau, Y. Li: A Cross-Cultural Study: Effect of Robot Appearance and Task. Int J Soc Robot 2(2):175–186, 2010.