NASA's Infrared Survey Telescope Ready to Retire

NEOWISE's enduring infrared eyes, which faithfully scanned the entire sky a whopping 23 times and observed more than 190,000 solar system objects, have closed for good

This article was first published on

www.caltech.eduNearly 15 years ago, a relatively small spacecraft about the size of a polar bear launched into space with a big mission: to map the entire sky at infrared wavelengths with a sensitivity up to hundreds of thousands of times better than previous surveys. The NASA mission, called WISE (Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer), far exceeded expectations, scanning the skies not once but twice and leaving behind a massive trove of data covering more than 740 million asteroids, stars, galaxies, and other cosmic objects. Ultimately, the telescope ran out of the coolant needed to chill its sensitive infrared detectors and was put into hibernation in 2011.

This video celebrates the legacy of NASA's NEOWISE mission, which has retired after more than a decade of discovering, tracking, and characterizing near-Earth objects.

But that was not the end of the story for the little telescope that busted open the infrared skies. After WISE's coolant ran out and it warmed up, two of the spacecraft's four infrared-wavelength bands still worked—bands that exceled at finding faint near-Earth asteroids and comets. So, in 2013, after nearly three years of hibernation, NASA woke WISE back up. The spacecraft was given a new name—NEOWISE (Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer)—and a new goal: to aid planetary defense by surveying and studying asteroids and comets that stray close to our neck of the solar system.

"I remember a bunch of us huddling around a terminal in 2009 as the first WISE images came in," says Roc Cutri, lead scientist and task lead for NEOWISE at Caltech's IPAC astronomy center. "And then I remember doing the same thing when NEOWISE turned back on in 2013. We were thrilled all over again."

Now, those enduring infrared eyes, which faithfully scanned the entire sky a whopping 23 times and observed more than 190,000 solar system objects, have closed for good. Solar activity is causing NEOWISE to fall out of orbit. Explosive flares and other eruptions on our Sun cause Earth's upper atmosphere to heat up and expand, which has slowed the satellite down.

"The Sun is waking up again after being quiet for a long time," says Cutri, referring to our Sun's current solar maximum. "We appreciate the cooperation of the Sun because it's given NEOWISE more time to operate, but the spacecraft is destined to reenter our atmosphere and burn up." Mission specialists say this is likely to occur near the end of this year.

Teams at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), which manages the mission, and Caltech's IPAC, the center responsible for data processing and archiving, are now preparing for the mission's end. On July 31 of this year, the spacecraft stopped collecting images of the sky. After collecting the final images and returning the spacecraft to hibernation, NEOWISE engineers at JPL issued a final command to turn off the transmitter on August 8.

"This is a bittersweet moment. It's sad to see this trailblazing mission come to an end, but we know there's more treasure hiding in the survey data," said Joe Masiero, NEOWISE's deputy principal investigator and a scientist at IPAC, in a JPL news story. "NEOWISE has a vast archive, covering a very long period of time, that will inevitably advance the science of the infrared universe long after the spacecraft is gone."

During its decade-plus run, NEOWISE captured nearly 27 million infrared images. It discovered 215 near-Earth objects and observed thousands more (NEOs are defined as asteroids and comets that pass within 28 million miles of Earth's path around the Sun). In addition to near-Earth asteroids, it found tens of thousands of asteroids in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter.

The mission spotted Earth's first known Trojan asteroid, which is an asteroid that rides along in the same orbit as our planet, and it discovered the celebrated comet C/2020 F3 NEOWISE, which adorned the night skies for onlookers in the Northern Hemisphere in the summer of 2020.

What's more, the mission's legacy will live on in a new mission currently in development. NASA's NEO Surveyor (Near-Earth Object Surveyor), scheduled to launch in late 2027, will be the first purpose-built infrared space telescope dedicated to hunting hazardous near-Earth objects.

"When I first started working on the original WISE mission in 2003, it was clear that it would teach us a lot about asteroids and comets, but it wouldn't be able to see huge numbers of Earth-approaching near-Earth objects," says Amy Mainzer, a professor at UCLA and the principal investigator of both NEOWISE and NEO Surveyor. "We've leveraged what we've learned from WISE and its extension, NEOWISE, to develop a new mission, NEO Surveyor, that is optimized for finding the most dangerous asteroids and comets. While we're getting ready to say goodbye to NEOWISE, we're looking forward to getting its powerful successor up into space in a few years."

Early Days

Originally proposed as the Next Generation Sky Survey, WISE was selected for flight in 2004 and given its current name. It was designed to succeed past infrared sky surveys with a dramatically improved level of sensitivity, and to ultimately unveil hundreds of millions of hidden cosmic objects that had never been seen before.

Infrared light, which has longer wavelengths than visible light, is invisible to our eyes. Our bodies are aglow with infrared light that we can't see. Many objects in the cosmos—asteroids, comets, cool stars, dusty planetary disks of debris, remote galaxies, and powerful quasars—shine brightly in infrared light but remain faint and hard to see in visible light. These objects tend to be older, cooler, obscured in dust, or hiding in the remote universe. Infrared surveys of the sky allow us to cast a wide net and catch these cosmic wonders.

Caltech's first infrared sky survey, called the Two-Micron Sky Survey, scanned the skies from a telescope atop Mount Wilson in the late 1960s. The Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) followed next, surveying the skies in infrared light from space in 1983. Later, from 1997 to 2001, the Two Micron All-Sky Survey (2MASS) mapped the whole sky from the ground. Caltech and IPAC, including the so-called Infrared Army, a group of scientists who pioneered infrared astronomy, played a key role in these groundbreaking projects.

"Caltech has a great history in infrared astronomy, so it was natural for us to be involved in WISE," says Cutri, who remembers working on WISE mission proposals in the late 1990s with the mission's principal investigator, Ned Wright, an astronomy professor at UCLA.

Rare Gems

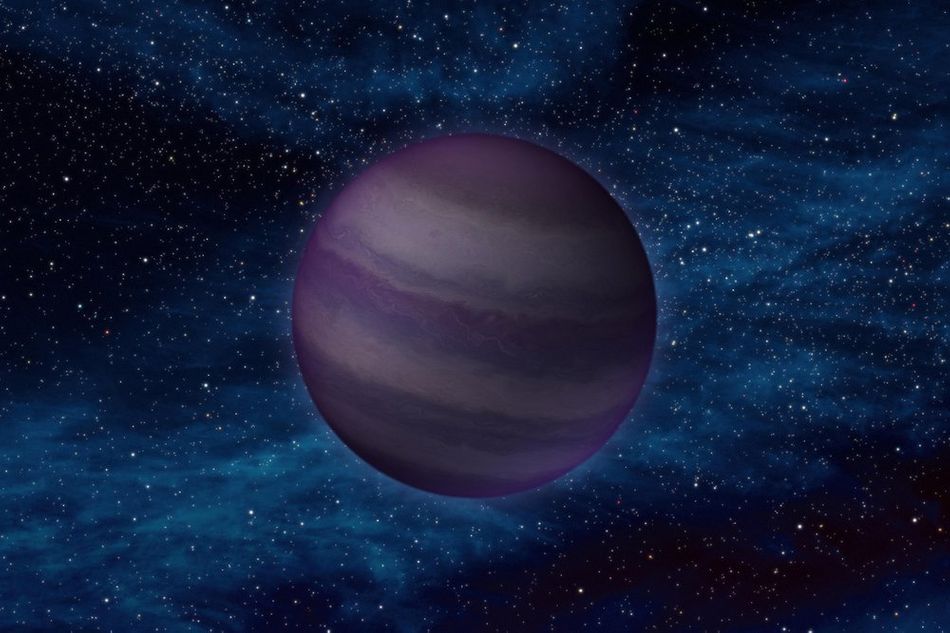

The two defining goals of the WISE mission were to find the closest stars to the Sun as well as the most luminous galaxies in the universe, both of which it achieved. In 2013 and 2014, astronomer Kevin Luhman of Penn State University used data collected by WISE to discover the third- and the fourth-closest star systems to Earth, lying 6.5 and 7.2 light-years away, respectively. Both systems contain cool stars known as brown dwarfs, and the fourth closest star, called WISE 0855-0714, also happens to be the coldest known brown dwarf with temperatures nearly as cold as ice.

In total, the mission found more than half of the known 582 brown dwarfs in our solar neighborhood, or specifically within 65 light-years of the Sun. (Nearly 20 percent of those 582 brown dwarfs were found by citizen scientists using WISE/NEOWISE data in a program called Backyard Worlds.) Before WISE, little was known about these celestial orbs, which form like stars but lack the mass to sustain the fusion that powers stars. The first brown dwarf was discovered in 1994 by a team led by Caltech's Shri Kulkarni using the 60-inch telescope at Palomar Observatory.

"We knew WISE was looking at the right infrared wavelength to bust the field open," says Davy Kirkpatrick, the IPAC lead for the WISE/NEOWISE quality assurance team and a WISE science team member.

Kirkpatrick remembers well the day he first laid eyes on the coolest class of brown dwarfs, called Y dwarfs. Previously, these extra-feeble stars had only been theorized.

"Mike Cushing [an astronomer at the University of Toledo] and I rented a condo in Hawai'i near the Keck telescope to follow up on brown dwarfs identified by WISE," Kirkpatrick recalls. "I was reducing a good-looking spectrum, and then my mouth just hung open. The chemical signatures of the first Y dwarf were right there. I yelled, 'Mike come here, we got one!' and he came running over."

Since then, the mission has discovered a total of 50 Y dwarfs, some of which were found during the NEOWISE phase of the mission (NEOWISE primarily focuses on asteroids and comets, but its data have also been used in a range of astronomy studies).

Farther from home, WISE uncovered tens of millions of actively feeding supermassive black holes, also known as quasars (Caltech's Maarten Schmidt discovered the first quasar in 1963). These monstrous cosmic entities are often buried in dust, rendering them invisible to optical telescopes. But the growing black holes warm their cloaks of dust, causing them to glow at the infrared wavelengths seen by WISE.

"WISE has shown that many, and perhaps most, quasars are buried in smoky cocoons," says Peter Eisenhardt, project scientist for WISE at JPL. "Our largest catalogs of quasars now come from WISE." Among these objects are rare and particularly warm and bright ones nicknamed hot DOGs, for hot Dust-Obscured Galaxies. One of these is likely the most luminous galaxy ever seen, shining with the light of 350 trillion suns.

"IRAS showed us that the most powerful nearby galaxies shine brightest in the infrared because they contain a lot of dust," Eisenhardt says. "As soon as we began mapping the sky with WISE, we tried all kinds of ways to find the most luminous galaxies in the universe with its four infrared bands, but we weren't finding much. Then, in April of 2010, we came across an extremely powerful galaxy that showed up only in WISE's two longest wavelengths: the first hot DOG. We adopted that technique and six months later found the most luminous galaxy of them all."

In addition to Y dwarfs, quasars, and hot DOGs, the WISE and NEOWISE catalogs are being used by astronomers around the world to study everything from comets and asteroids to distant clusters of galaxies. "WISE and NEOWISE data are now part of the astronomy landscape and are being used in over a thousand papers per year," Eisenhardt says.

Surprise Asteroid Hunter

When mission specialists turned the spacecraft back on in 2013, they did not expect it would still be going strong more than 10 years later. A mission designed to survey the whole breadth of the cosmos both near and far will be remembered for a decade of asteroid discoveries.

Thanks to NEOWISE's infrared vision, it will also be remembered for revealing a population of near-Earth objects that are extremely dark, like pieces of charcoal, and large, measuring hundreds of meters across, and in some cases larger. The mission's observations showed that such objects constitute a sizeable part of the overall NEO population.

"The dark objects make up a substantial fraction of the population, roughly a third, posing a challenge for ground-based telescopes searching for them in visible light" Mainzer says. "But they pop out in heat-sensitive infrared wavelengths."

To find more of these hidden dark rocks orbiting in our solar system as well as many other asteroids left to uncover, the NEOWISE team developed the upcoming NEO Surveyor.

"One of the goals for NEO Surveyor is to find the medium-size asteroids, which could still be hazardous to our planet," Cutri says. According to NASA, only 44 percent of these medium-size asteroids (140 meters and larger) have been found. "The motto has been to find them before they find us."

Like NEOWISE, NEO Surveyor's background data will also be used to study stars, galaxies, and other cosmic objects throughout the universe.

"When we started in the late '90s on this mission, if you told me that this spacecraft would still be taking data when I turned 60, and that we'd be working on a successor to the mission, I would have said, 'You are nuts,'" says Kirkpatrick, who plans to use the mission's data to look for even closer and cooler brown dwarfs than those discovered by WISE. "If anything, WISE and NEOWISE have taught us that just when you think you have reached the limit of what you can find, it is just the limit of the survey. More is out there to be found."

More about the Mission:

NEOWISE and NEO Surveyor support the objectives of NASA's Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO) at NASA Headquarters in Washington. The NASA Authorization Act of 2005 directed NASA to discover and characterize at least 90% of the near-Earth objects more than 140 meters (460 feet) across that come within 30 million miles (48 million kilometers) of our planet's orbit. Objects of this size can cause significant regional damage, or worse, should they impact the Earth.

JPL manages and operates the NEOWISE mission for PDCO within the Science Mission Directorate. The WISE principal investigator was Edward Wright, a professor at UCLA. The NEOWISE principal investigator is Amy Mainzer, also a professor at UCLA. The Space Dynamics Laboratory in Logan, Utah, built the science instrument. Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. of Boulder, Colorado (now BAE Systems), built the spacecraft. Science data processing, archiving, and distribution is done at IPAC at Caltech. Caltech manages JPL for NASA.