A Neglected Market: Why Industrial Obsolescence Is Accelerating?

The 80/20 Investment Imbalance Reshaping Semiconductor Supply

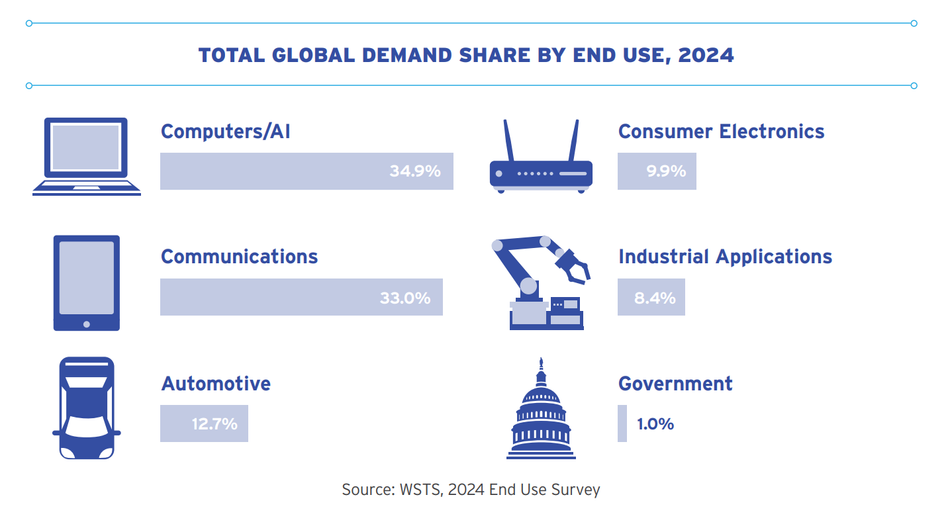

Investment in the semiconductor industry always flows in the direction of density. Over the last decade, a massive surge in capital expenditure has been directed toward three dominant sectors: Artificial Intelligence (data centers), portable consumer electronics (smartphones/laptops), and next-generation automotive ADAS (autonomous driving).

Together, these three categories now monopolize nearly 80% of global wafer-fab capacity. The remaining 20% is left to support all other sectors of the global economy, including aerospace, medical, and heavy industry (1). This 80/20 split creates a dangerous asymmetry. While industrial OEMs depend on stability and long-life design, the global supply chain is retooling exclusively for speed and scale.

The result is an accelerating erosion of supply continuity for sectors that still require decades of guaranteed availability.

The Problem of Stranded Technology

Modern semiconductor economics are predicated on scale. Integrated Device Manufacturers (IDMs) and foundries are constructing large facilities dedicated to advanced lithography nodes with the goal of maximizing the number of transistors per wafer. To recoup these immense capital costs, manufacturers must fill these lines with high-margin, high-volume products like AI processors or high-bandwidth memory. In this environment, traditional control logic, analog interfaces, and low-frequency microcontrollers have no clear path forward.

The contrast has widened since 2020! According to market analysis, nearly all new assembly and packaging investment has been directed toward 2.5D and 3D architectures designed for stacked die, chiplets, and flip-chip BGAs (2). These structures are incompatible with the lead-frame and through-hole packages that dominate industrial boards, and maintaining those older package lines requires equipment that few assembly vendors are willing to operate.

As production volume migrates, the cost to sustain an older process node or package type increases sharply. Eventually, the device no longer meets the revenue threshold that a semiconductor manufacturer must achieve to justify ongoing support.

This economic reality creates a quiet but deadly mechanism for obsolescence. The decision to shut down a process line or retire a specific package type is often made months before the customer is notified. By the time an industrial OEM receives a Last-Time-Buy notice, the fabrication tooling has likely already been reallocated, and the tester platforms reassigned. For companies managing fleets of equipment with decades of expected service life, the window to react effectively has usually closed before they are even aware of the problem.

The Volume Paradox

The industrial sector finds itself in a unique and difficult position regarding leverage. Industrial machines represent a massive capital investment at the system level. An excavator or a factory automation system costs significantly more than a consumer device. However, the sheer volume of semiconductors required by these machines is nothing compared to the billions of smartphones or tens of millions of passenger vehicles produced annually. Consequently, industrial requirements rarely drive design or manufacturing priorities at the chip level.

Fabs have forgotten the industrial sector because of a conflict in business models. Industrial designers have prioritized consistency to guarantee software compatibility, safety certifications, and regulatory compliance for decades. In contrast, the semiconductor ecosystem is built for churn and rapid advances.

This gap creates practical hurdles on the factory floor. Equipment designed to handle twelve-inch wafers cannot be easily repurposed for eight-inch production, and maintaining dual infrastructures is rarely financially viable. As suppliers convert lines to advanced logic or automotive sensors, the specific processes and packaging formats that industrial customers rely on are left without a manufacturing home.

The Risks of Change

For industrial OEMs, the retirement of these technologies introduces a complex interplay of risks (3). The most immediate consequence is the loss of supply, where compatible replacements simply do not exist because the underlying process technology has been retired.

However, the secondary effects are often more costly. Engineers often deploy industrial systems in dozens of countries, each with its own safety and emissions standards. Replacing even one microcontroller or interface IC can necessitate requalification of the entire machine to prove functional equivalence. The process can consume months of engineering time and significantly impact revenue.

Perhaps the most significant, yet overlooked, risk involves software dependence. Many industrial OEMs develop the hardware automation systems, but it's the end customer that develops and maintains the control software. This software often relies on specific hardware behaviors established years ago. A forced hardware modification can invalidate years of field-proven code and necessitate a rewrite that the hardware supplier cannot perform and the customer may not be equipped to handle.

It’s clear why industrial customers fiercely resist design changes. Beyond protecting hardware, the integrity of a software ecosystem cannot be easily replicated.

The Economic Value of Continuity

The financial argument for maintaining legacy semiconductors often receives less attention than the technical one. In industrial operations, unplanned obsolescence can halt production lines worth millions per day. Procuring authentic replacement parts through unauthorized channels may introduce counterfeit or degraded devices, thereby compounding the risk. Licensed continuation through an authorized source eliminates that uncertainty and protects both quality and traceability.

Rochester’s goal is to address the rift between short-cycle semiconductor production and the long-cycle needs of industrial customers. For example, Rochester actively purchases inventory throughout discontinuation cycles and maintains wafer and die stock for devices that would otherwise vanish. Thanks to licensed manufacturing agreements with major OCMs, Rochester sustains production of legacy parts long after the original supplier has exited.

For OCMs, the relationship with Rochester improves their brand reputation beyond the normal sales horizon. A device that continues to ship reliably twenty years after its introduction reinforces the manufacturer’s credibility with high-reliability markets. For OEMs, that continuity translates into lower total cost of ownership and reduced regulatory exposure. Replacing a controller might seem minor on paper. Still, if the change triggers new safety validation or emissions testing across dozens of countries, the expense can dwarf the price of the part itself.

Looking Ahead

As semiconductor investment continues to consolidate around high-volume consumer and AI applications, Rochester’s proactive approach is the only way for industrial manufacturers to secure their future.

References

1. https://www.semiconductors.org/2025/07/SIA-State-of-the-Industry-Report-2025.pdf

2. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2310.11651

3. https://www.rocelec.com/news/shifts-for-long-lifecycle-applications