Orbit 100,000 for TerraSAR-X radar satellite

The German radar satellite TerraSAR-X will complete its 100,000th Earth orbit on 26 June 2025.

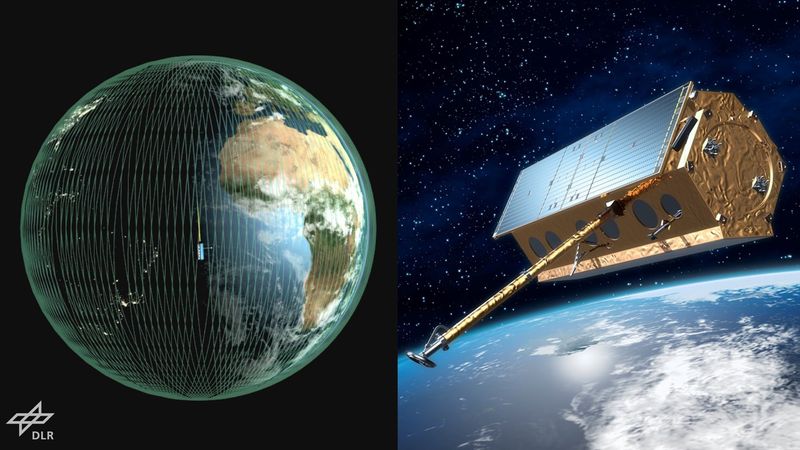

Artist's impression of the German Earth observation satellite TerraSAR-X and its orbit around Earth. Credit: DLR (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

This article was first published on

www.dlr.deA special 'service anniversary' in German spaceflight: On 26 June 2025, starting at 23:33 CEST, TerraSAR-X will orbit Earth for the 100,000th time. For 18 years, the radar satellite operated by the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) has been circling the globe at an altitude of 514 kilometres – travelling from the equator to the North Pole, back to the equator on the other side of our planet and down to the South Pole in just under 95 minutes. Over the course of 100,000 orbits, it has travelled approximately 4.3 billion kilometres – roughly the distance from Earth to Neptune, the outermost planet in our Solar System, when the two are at their closest.

Between 2007 and 2025, TerraSAR-X has produced over 350,000 SAR images of unprecedented quality. SAR stands for the imaging technology used – Synthetic Aperture Radar. As the satellite passes overhead, its radar continuously observes a target area on Earth for approximately half a second. Back on the ground at DLR's facilities, the data transmitted is used to compute a sharp SAR image. This mathematical method achieves the same effect as a four-kilometre-long antenna in space. Only such a large antenna could achieve a resolution of up to one metre and generate images in such fine detail. Flying in close formation with its three-years-younger twin satellite TanDEM-X, TerraSAR-X also maps a relief of Earth's surface to generate digital elevation models.

Earth's surface through the ages

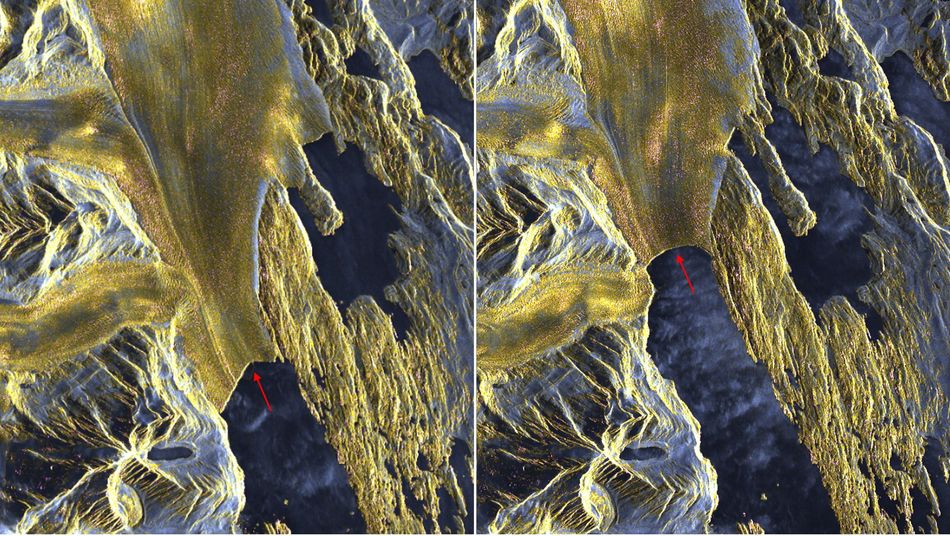

This first image shows the Upsala Glacier in the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, straddling the border of Chile and Argentina. The left-hand image was taken in January 2008, at the start of TerraSAR-X's operational phase. The right-hand image is from March 2022. In that time, the Upsala Glacier has retreated by approximately five kilometres due to climate change – that is over five centimetres per TerraSAR-X orbit, or almost one metre per day.

Another TerraSAR-X image was taken over DLR's site in Oberpfaffenhofen on 28 October 2007, using the High-Resolution Spotlight mode. The region west of Munich was used to calibrate the satellite during the first six months after its launch to ensure the accuracy of its measurements. For this purpose, artificial targets with precisely known properties were set up. Such targets are used to continuously monitor satellite accuracy, even during routine operations. One of these targets can be seen as a bright cross in the right-hand image from 10 December 2024, near the runway of the Oberpfaffenhofen 'special airport'. Here, too, we see changes over time: a new federal highway has been built through the forest to the east of the airport, and many new buildings have sprung up around the site.

Although TerraSAR-X has already exceeded its original six-year mission lifetime by a factor of three, its measurement accuracy remains practically unchanged. There are several reasons for this: First, all the satellite's critical components have proven to be highly accurate and stable over the long term. Second, they are also duplicated – so if a control element fails, for example, the identical, still functional backup can take over. Third, the onboard computer software can be updated from the ground.

TerraSAR-X's fuel will still last for several more years. Provided there are no serious incidents – such as extremely strong solar storms or unforeseen collisions with space debris – TerraSAR-X will continue to clock up kilometres and deliver many more images. These will continue to be used by the public sector, scientific institutions and companies to monitor changes on Earth. Political decision-makers, disaster response agencies and others use this data to determine both short- and long-term courses of action.