Re-Architecting Additive Manufacturing for Scale

How Materialise is redefining software architecture as additive manufacturing moves into industrial production

Additive manufacturing (AM) has spent much of its history inside controlled environments. Research labs, prototyping departments, and specialist teams could tolerate complexity because expertise was concentrated and production expectations were limited. Today, that context has changed. Across industries from aerospace to defense, industrial equipment, and spare parts, AM is increasingly expected to function as a production technology rather than an experimental capability.

This transition has exposed a structural imbalance. 3D printer performance and material portfolios have matured steadily, yet the surrounding software infrastructure has struggled to keep pace. While specialized software has been good enough for small groups of highly skilled specialists, it now has to support distributed manufacturing organizations, integrate with enterprise systems, and operate at scale without constant expert intervention. In many deployments, software has emerged as the primary bottleneck for growth.

These observations frame how Materialise is approaching the next phase of AM. In a conversation with Bart Van der Schueren, Chief Strategy and Technology Officer, and Tom Craeghs, Director of Product Management, they shared that scaling AM requires the rethinking of software architecture itself, grounded in how manufacturing organizations actually operate today.

From Isolated AM Departments to Distributed Production

For much of its early evolution, AM software was designed as a technical toolbox. These environments assumed deep user knowledge and allowed engineers to experiment directly with parameters, geometry preparation, and process tuning. That model functioned well in protected settings, where a small number of specialists controlled the entire workflow.

AM is now moving into mainstream production contexts. New roles are involved, including operators, planners, quality engineers, and sales teams. These users interact with AM as part of a broader digital manufacturing thread rather than as an isolated process. Software that depends on continuous expert intervention becomes difficult to scale under those conditions.

The challenge is not simplification in the sense of eliminating complexity from the process. AM remains inherently complex. Instead, the challenge lies in presenting that complexity in a way that different roles can interact with reliably, without requiring everyone to become an AM specialist. This shift changes what software has to do. It must orchestrate workflows, preserve expertise, present a sufficient level of explainability, and integrate seamlessly with other manufacturing systems.

These requirements represent a structural integration issue, especially when deploying AM at scale. AM software has historically developed its own domain language, shaped by build preparation, slicing, and process parameters. Manufacturing IT systems operate with varying abstractions, focusing on orders, routings, quality records, and traceability.

When these two worlds fail to align, integration becomes fragile. Data moves between systems through manual steps or brittle interfaces, limiting automation and increasing operational risk. Bridging this gap requires going beyond technical connectors and into a shared architectural model that allows AM concepts to be expressed and understood within the broader manufacturing context.

Materialise treats this mapping as a first-order design problem. The goal is to allow AM to function as a native component of manufacturing operations, rather than as a specialized exception that sits alongside them.

Rethinking the Role of End-to-End Platforms

Industry discussions around AM software have often emphasized end-to-end platforms. The promise has been consistency and control across the workflow, from design intake to finished part. Materialise’s experience with industrial deployments has led to a more nuanced position.

Van der Schueren describes this approach using a T-profile analogy. The horizontal axis represents an end-to-end workflow that can take a design through production with full traceability. The vertical axis represents deep AM expertise, built from decades of algorithm development and process knowledge.

Some organizations benefit from adopting the full horizontal workflow, particularly when they lack existing manufacturing systems. Others already operate mature ERP, MES, and PLM infrastructures and only require access to additive-specific capabilities. Materialise’s software architecture is designed to support both cases, allowing companies to adopt a complete workflow or integrate selected components into their existing systems.

This architectural choice reflects an acknowledgment of manufacturing reality. Most industrial environments are heterogeneous. For AM to scale, software must accommodate that diversity rather than attempt to replace it.

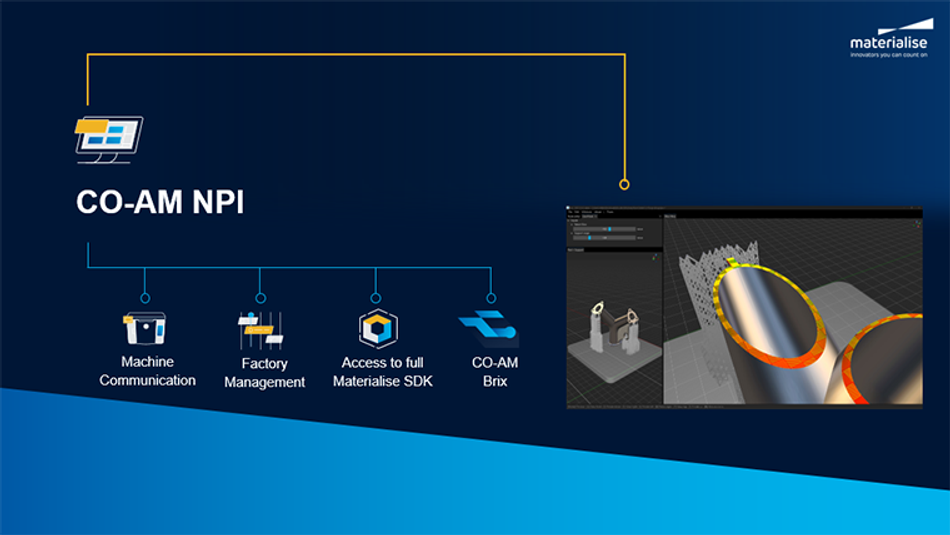

At the foundation of this approach sits Materialise Magics, which continues to serve as the production-proven core for data and build preparation. Building on this foundation, the Co-AM platform extends Magics into an open, modular software architecture that connects workflows, users, machines, and enterprise systems. Within this platform, Brix operates as an automation and orchestration layer, enabling customers to translate deep AM expertise into executable, reusable workflows rather than fixed sequences of manual steps.

Materialise summarizes this philosophy internally as “your process, your rules.” It reflects a deliberate decision to let customers define how AM fits into their operations, instead of forcing diverse production realities into predefined software workflows.

Why Additive Manufacturing Resists Abstraction

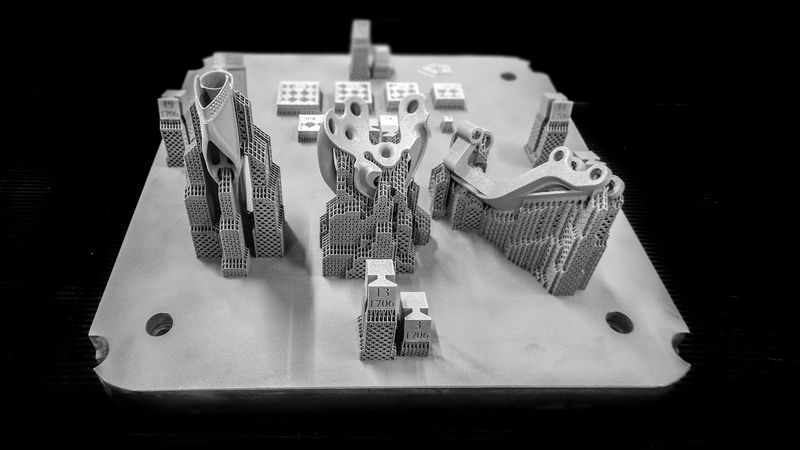

One reason AM software has proven difficult to generalize lies in the physics of the process itself. Unlike conventional manufacturing, where material properties are largely defined before shaping occurs, AM produces geometry and mechanical performance simultaneously. Orientation, support strategy, scan parameters, and thermal history interact continuously, shaping both the form of a part and its functional behavior.

This coupling creates a level of process interdependence that resists simplification through generic abstractions. Van der Schueren notes that this reality fundamentally shapes how Materialise approaches usability. The objective is not to eliminate complexity but to make it legible and controllable. Software must expose the right degrees of freedom without requiring every user to engage at the same technical depth.

These constraints manifest differently across production contexts. In high-mix, low-volume applications such as prototyping, on-demand spare parts, and certain defense programs, the central challenge tends to be decision reliability. Organizations must assess feasibility consistently, prepare builds predictably, and reuse validated process knowledge across a large number of unique parts. Scalability in these environments depends less on throughput than on how effectively expertise can be formalized and distributed beyond a small group of specialists.

Series production introduces a distinct economic pressure. While AM can support production volumes in the thousands and, in some cases, even millions of parts, most applications operate well below the scale at which traditional manufacturing amortizes new product introduction (NPI) costs. Even when volumes reach the tens of thousands, NPI effort often remains a dominant factor in the business case. This explains why many AM applications succeed technically yet struggle to remain economically viable once sustained production begins.

From Materialise’s perspective, this is where software becomes a decisive lever. Many business cases do not fail because AM cannot deliver functional parts but because the path from development to economical production remains too long or too opaque. Software that reduces the effort required to optimize parameters, refine support strategies, and iterate on design and process choices can shorten the NPI phase and make incremental cost improvements meaningful at moderate volumes. In this context, higher-volume AM becomes less about reproducing mass production economics and more about systematically lowering the threshold at which series production becomes economically viable.

Across both low-volume and series contexts, customers increasingly seek ownership of their processes. Moving beyond fixed parameter sets allows organizations to adapt AM to their specific technical and economic constraints, rather than conforming their applications to predefined workflows.

Co-AM Brix and the Operationalization of Expertise

Materialise’s investment in Brix addresses this demand for process ownership directly. Brix is a visual programming environment built on Materialise’s software development kit (SDK), which now contains more than a thousand AM algorithms developed over more than three decades.

Rather than exposing these capabilities exclusively through expert-centric tools, Brix allows process engineers to assemble validated workflows visually, observe outcomes immediately, and deploy those workflows across an organization. In high-mix, low-volume environments, this enables organizations to automate decision-making and standardize preparation steps without diluting expertise.

A process engineer can, for example, encode feasibility checks, orientation logic, or quality constraints into a Brix workflow. Sales teams or front-line engineers can then apply that workflow automatically to incoming parts, receiving consistent assessments without requiring direct expert intervention. Standards are preserved, response times improve, and expertise scales across the organization in a controlled manner.

In series production contexts, Brix serves a complementary function. Engineers use it to explore interactions between design choices, support strategies, and process parameters within a unified environment. While the underlying complexity remains, its behavior becomes observable, allowing development teams to understand trade-offs more clearly and converge on robust production strategies faster.

This capability is particularly relevant for original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) that already operate internal AM centers. As Craeghs explains, these groups often serve as incubators for new applications, supporting prototyping and limited production long before series manufacturing is viable. Materialise’s role is to help these organizations translate internal expertise into repeatable, scalable workflows that can survive the transition from experimental capability to sustained production. By reducing operational friction and uncertainty, software becomes the mechanism through which AM moves from isolated competence to industrial infrastructure.

A Gradual Transition Shaped by Product Redesign

Van der Schueren and Craeghs describe the current phase of AM as a measured transition rather than a sudden inflection. The most successful applications emerge when products are redesigned specifically for AM, not adapted from conventional designs. Such redesign cycles take time.

As products developed over the past decade begin to move into production, their success creates a multiplier effect. One validated application leads to additional machines, more automation, and deeper integration into manufacturing operations. That progression reinforces the need for software architectures that can scale without centralizing expertise.

Materialise positions itself within this evolution as a solution provider. Its focus lies in translating deep AM knowledge into systems that organizations can operate, adapt, and trust over time.

The long-term trajectory of AM depends on the accumulation of reliable, repeatable production experience. Software sits at the center of that accumulation, defining how knowledge is captured, workflows executed, and AM connected to the rest of the factory. This evolution requires openness, modularity, and an architectural discipline informed by decades of domain expertise. With AM’s gradual integration into production, the companies that succeed will be those that treat software as the foundation upon which scale is built.

For more information about Materialise’s approach to AM, visit www.materialise.com