Synthetic tooth enamel may lead to more resilient structures

Tooth enamel has changed very little over millions of years -- and it is remarkably resistant to shock and wear.

Wenfeng Jiang demonstrates the process of growing the zinc oxide nanopillars and layering the polymer over them. Credit: Evan Dougherty, Michigan Engineering Communications & Marketing.

USING NANOWIRES TO CREATE SYNTHETIC ENAMEL Michigan Engineering professor Nicholas Kotov explains how he and his team developed a rigid and durable new material inspired by tooth enamel.

Unavoidable vibrations, such as those on airplanes, cause rigid structures to age and crack, but researchers at the University of Michigan may have an answer for that: Design them more like tooth enamel. It could lead to more resilient flight computers, for instance.

Most materials that effectively absorb vibration are soft, so they don’t make good structural components such as beams, chassis or motherboards. For inspiration on how to make hard materials that survive repeated shocks, the researchers looked to nature.

“Artificial enamel is better than solid commercial and experimental materials that are aimed at the same vibration damping,” said Nicholas Kotov, the Joseph B. and Florence V. Cejka Professor of Chemical Engineering. “It’s lighter, more effective and, perhaps, less expensive.”

He and his team didn’t settle on enamel immediately. They examined many structures in animals that had to withstand shocks and vibrations: bones, shells, carapaces and teeth. These living structures changed from species to species and over the eons.

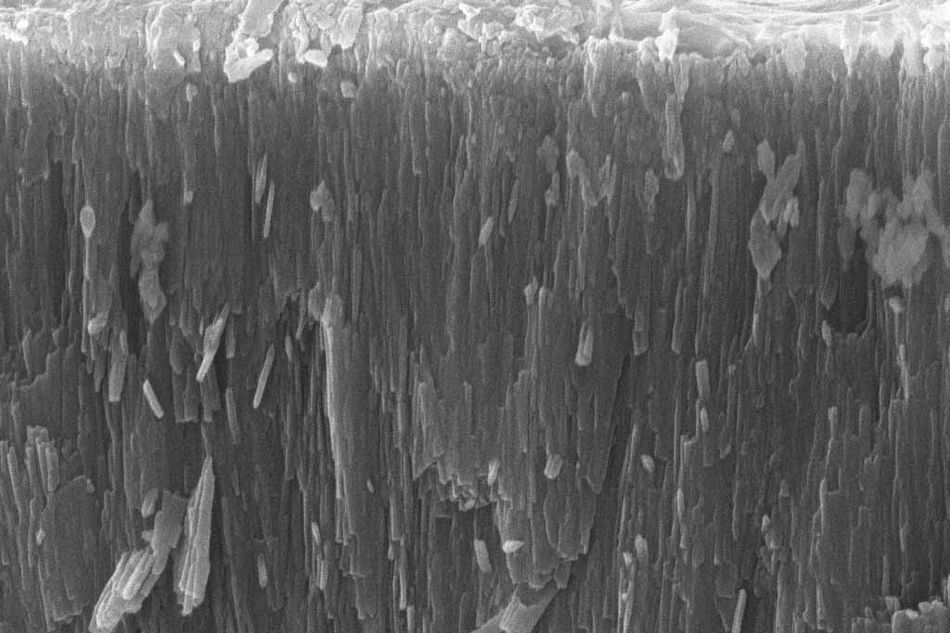

Tooth enamel told a different story. Under an electron microscope, it shared a similar structure whether it came from a Tyrannosaurus, a walrus, a sea urchin or a human.

An electron microscope image of human tooth enamel. Credit: Kotov Lab, University of Michigan.

“To me, this is opposite to what’s happening with every other tissue in the process of evolution. Their structures diversified tremendously but not the structure of enamel,” said Kotov.

Evolution had hit on a design that worked for pretty much everyone with teeth. And unlike bone, which can be repaired, enamel had to last the lifetime of the tooth – years, decades or longer still. It must withstand repeated stresses and general vibrations without cracking.

Enamel is made of columns of ceramic crystals infiltrated with a matrix of proteins, set into a hard protective coating. This layer is sometimes repeated, made thicker in the teeth that have to be tougher.

The reason why this structure is effective at absorbing vibrations, Kotov explained, is that the stiff nanoscale columns bending under stress from above create a lot of friction with the softer polymer surrounding them within the enamel. The large contact area between the ceramic and protein components further increases the dissipation of energy that might otherwise damage it.

Bongjun Yeom, a post-doctoral researcher in Kotov’s lab, recreated the enamel structure by growing zinc oxide nanowires on a chip. Then he layered two polymers over the nanowires, spinning the chip to spread out the liquid and baking it to cure the plastic between coats.

It took 40 layers to build up a single micrometer, or one thousandth of a millimeter, of enamel-like structure. Then, they laid down another layer of zinc oxide nanowires and filled it in with 40 layers of polymer, repeating the whole process up to 20 times.

Even molecular or nanoscale gaps between the polymer and ceramic would reduce the strength of material and the intensity of the friction, but the painstaking layering ensured the surfaces were perfectly mated.

“The marvelous mechanical properties of biological materials stem from great molecular and nanoscale adaptation of soft structures to hard ones and vice versa,” said Kotov.

Kotov’s group demonstrated that their synthetic tooth enamel approached the ability of real tooth enamel to defend itself from damage due to vibrations. Computer modeling of the synthetic enamel, performed by researchers at Michigan Technological University and the Illinois Applied Research Institute, confirmed that the structure diffused the forces from vibrations through the interaction between the polymer and columns.

From the project’s inception as a challenge from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Kotov worked with fellow materials heavyweights Ellen Arruda, a professor of mechanical engineering, and Anthony Waas, the Felix Pawlowski Collegiate Professor Emeritus.

Kotov hopes to see the synthetic enamel deployed in airplanes and other environments in which vibrations are inescapable, protecting structures and electronics. The challenge, he says, will be automating the production of the material.