Toughened hydrogels could replace cartilage, skin and more

U-M formula and process allow for the creation of devices and materials for precision medicine.

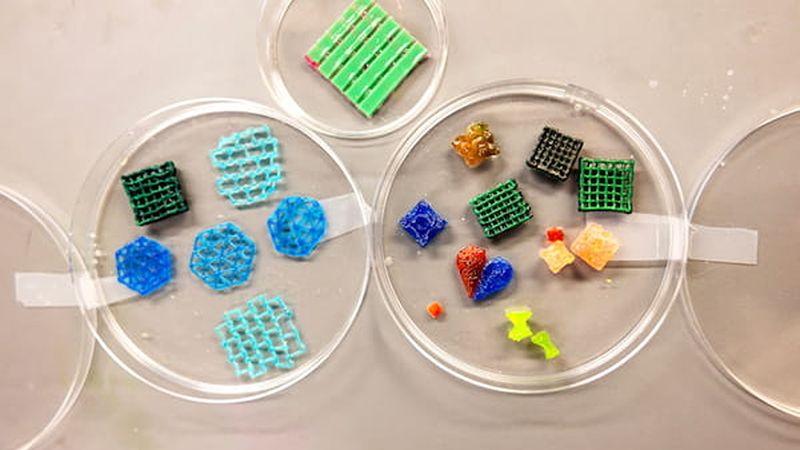

Close up of various colorful hydrogel samples arranged in multiple petri dishes on a lab bench, showing different shapes and textures, at the lab of Sungmin Nam and Jihun Lee at the GG Brown building.

This article was first published on

news.engin.umich.eduThere are parts of the body that science has found particularly hard to replace or restore, whether it’s because of the natural attributes they possess or their location inside us.

Take the cartilage in your knee—a substance that wears down through aging, repeated use and injury. Or consider the skin that covers your elbow. For burn victims, even skin grafted from other parts of the body won’t ever feel or perform the same.

In both cases, science has yet to come up with a long-term replacement that allows for similar flexibility and durability. But hydrogels, “toughened” by researchers at the University of Michigan, hold the promise of providing tools that can replace and supplement cartilage, skin, collagen or other materials in the body.

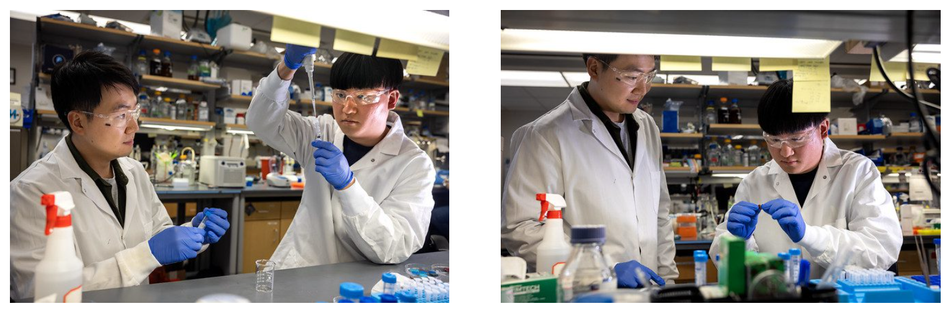

“Hydrogels are very good at mimicking the tissue environment, both mechanically and biochemically,” said Sungmin Nam, a U-M assistant professor of mechanical engineering. “So we use them as engineering tools that can be placed safely in the body.”

And once on, or in, the body, they’re capable of providing a framework for cellular growth, delivering medicine and acting as a protective layer. These toughened hydrogels can be used to create soft robots and medical devices, or even replace surgical sutures.

Hydrogels are natural or synthetic polymers—large molecules, composed of repeated smaller units, in large networks—capable of taking in and holding water. They’re utilized in a variety of products, including contact lenses, medical dressings, gelatins and soil additives in agriculture. In case you didn’t realize it, gummy bears are a hydrogel.

Their uses have been limited, however, due to their makeup—tyically being composed of more water (as much as 90%) than polymer—which makes them too weak for some uses. Such uses could include places in the body that see repetitive stresses like knee joints, or places where elasticity is key, such as the skin at the elbow.

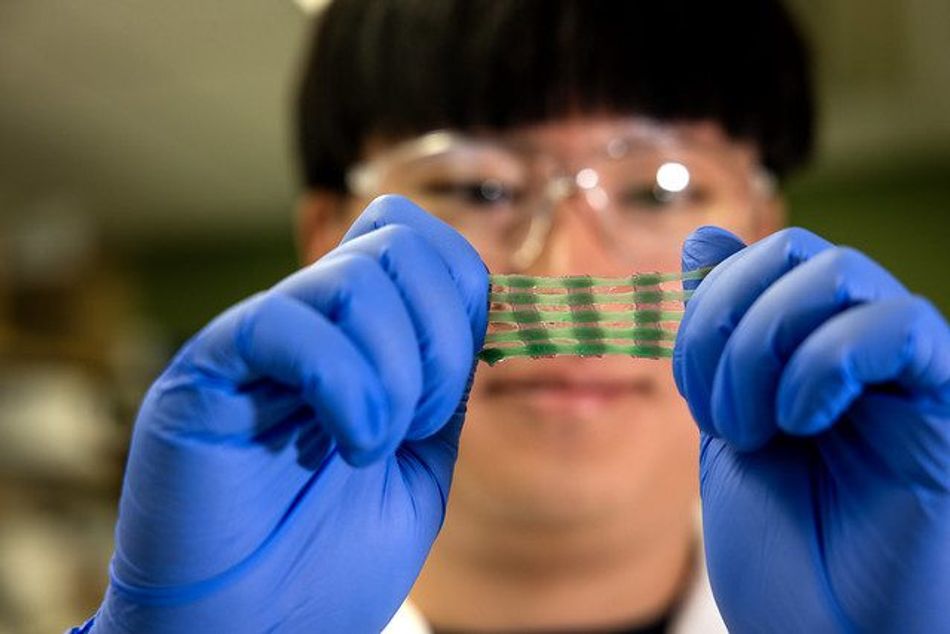

Nam and Jihun Lee, a graduate student in mechanical engineering, have successfully strengthened hydrogels by using a combination of components: a complex carbohydrate, or alginate, derived from brown algae and infused with calcium, and a highly-absorbent polymer called polyacrylamide.

“When we bring those two components together, interestingly, they work in synergy to make the hydrogel mechanically very tough,” Lee said. “In addition to simply becoming tougher, our approach enables mechanical reinforcement at desired locations and at desired times,”.

Their tougher hydrogels can essentially be programmed with a variety of characteristics, including adhesiveness and electrical conductivity. These additional functionalities greatly expand the potential applications of the material. For example, the combination of high mechanical strength and strong tissue adhesion could potentially replace surgical sutures in future clinical procedures.

They can also be loaded with therapeutic agents, mechanically protecting the payload and enabling controlled, long-term release. For Rogerio Castilho, a U-M professor of dentistry and collaborator, it’s the definition of precision medicine.

“Using a 3D bioprinter, we can create with any of these toughened hydrogels, incorporating different types of cells,” Castilho said. “We can incorporate drugs that will lead one cell type to proliferate more. We can print layers of these cells, or different cells in different layers, giving us the shape and format we want.

“You can print exactly what’s needed for an individual patient simply by referencing an MRI or a CT scan. One notable feature of these hydrogels is that they are not only mechanically tough but also highly stretchable—much like rubber—and remarkably resilient.”

U-M researchers have filed a provisional patent application for their toughening method.

“We are in close discussion with clinicians at Michigan Medicine to identify medical contexts in which this hydrogel could have the greatest impact,” Nam said. “Once we confirm its biocompatibility and efficacy in animal models, we plan to work together to determine how this material could be practically applied in patient care.”